PLAT 11.5 ORDINARY

1 Tim Ingold. “Culture on the Ground: The World Perceived through the Feet,” in Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description (New York: Routledge, 2021), 51.

2 Ingold, “Culture on the Ground,” 54.

3 “Uniform Color Code 2020,” American Public Works Association, accessed August 26, 2023, Link

4 Ingold, “Culture on the Ground,” 55.

5 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, “The Life of the Forest,” in The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015), 160.

6 Tsing, “Life of the Forest,” 160.

Gwendolyn

Dora

Cohen

Our municipal streets and sidewalks are often paved with asphalt and concrete. These continuous surfaces provide a relatively smooth and predictable place for walking: each step follows the previous and the surface of the ground disappears into the ordinary. Without having to carefully navigate over cobblestones or potholes, we can easily forget that our streets and sidewalks are designed, built, and maintained.1 We can forget the fact that their existence requires care—even concrete doesn’t last forever. But if we pay attention, the actions of our cities’ maintainers reveal the complex world below our feet. If we pay attention, we can read the histories of maintenance that keep our streets and sidewalks functioning—in the realm of the invisible and the ordinary.

When considering our perception of the environment while walking along a street, anthropologist Tim Ingold states: “(i)t appears that people, in their daily lives, merely skim the surface of a world that has been previously mapped out and constructed for them to occupy, rather than contributing through their movements to its ongoing formation. To inhabit the modern city is to dwell in an environment that is already built.”2 The following series of photographs acknowledges that our communities are built and persistently maintained by individuals, who are often unrecognized, but who leave their individual mark on the surfaces of our streets—those who are crucial to the “ongoing formation” of our cities.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

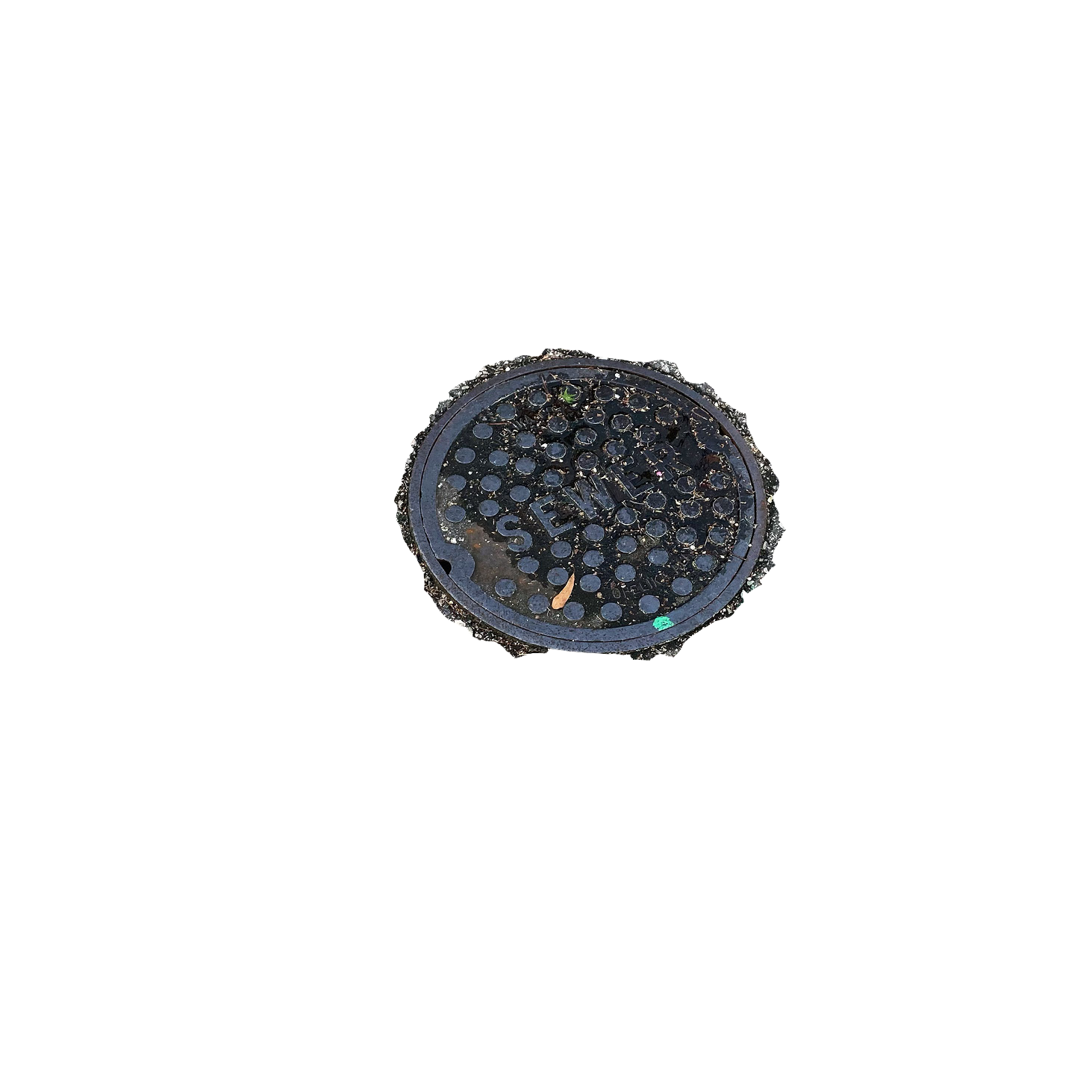

In an incredibly legible way, the spray paint marks created by utility locators reveal hidden infrastructure to those who notice. The American Public Works Association has developed a uniform color code for temporarily marking utility lines.3 Here, the green paint indicates sewer lines below the asphalt. The arrows indicate the direction of flow, and while walking along the street, one can begin to trace the sewer system as each utility cover is marked with an arrow to indicate subterranean connections.

![]()

![]()

![]()

For each home football game at Auburn University, hundreds of tailgating tents are installed throughout campus. About a week before the first game, utility locators mark the ground with spray paint to indicate the location of each pipe and conduit. The paint appears on nearly every lawn across campus, signaling the arrival of the season with its vibrant colors and lingering paint fumes. These utility marks ensure that no tent stakes disrupt the belowground network.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Beyond utility marking, colors on the ground can also indicate the presence of herbicide. Before application, a blue-green pigment is added to the herbicide solution. This pigment washes away in the rain, and is only intended to last long enough for the applicator to note where it has been applied. Before the herbicide takes action, in a last unintentional celebration of life the color briefly brings attention to these unwanted plants before they die.

![]()

![]()

Cracks develop in our asphalt streets as the ground shifts and above-ground forces weaken the surface. To repair these cracks, maintainers trace them with asphalt crack filler. In the application of this filler, the patterning of the cracks is revealed, while the personal style of the maintainer also becomes evident. From precise applications to broad “brush strokes” that seem to dance from one crack to another, the asphalt crack filler becomes a paintbrush in the hands of the maintainers. While the presence of the asphalt crack filler might signal degradation to some, it can also be perceived and celebrated as an act of care for our built environment.

Sometimes to maintain our landscape, subtraction is required instead of addition. When concrete cracks and lifts, a grinder can be used to remove protrusions to form a continuous surface again. This act of removing a portion of the lifted concrete reveals its internal structure — often the aggregate — and contrasts with the finished surface of the surrounding concrete. This contrasting band reveals the history of movement and the history of maintenance. One might consider this an indication of what was broken, but one might also see it as a necessary act of care for our landscape. These marks reveal that nothing is static, our landscape—even the paved surfaces—is always evolving.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When simple grinding or patching of the surface isn’t enough, entire areas of concrete are often removed and repoured. Rarely is there an effort to match the color or aggregate of the adjacent concrete. The replacement concrete is often mixed from (and therefore, records) the most readily available sand and aggregate from the time it was poured. Its surface texture is then determined by the installer, who applies their preferred approach to achieve either a broom or trowel finish. For a while, the replacement concrete appears distinctively different from the concrete adjacent to it. It reveals an act of maintenance and records the hands of its installer.

Each of these moments of maintenance and marking exists in the ordinary. “For it is surely through our feet, in contact with the ground, that we are most fundamentally and continually ‘in touch’ with our surroundings.”4 By choosing to walk, and choosing to observe, we engage with the world. Each of these photographs captures a moment of noticing.5 Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing considers human-disturbed landscapes to be ideal places for “noticing.” And in itself, “disturbance is ordinary.”6

Gwendolyn Cohen is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Auburn University. She graduated from the University of Virginia with a Master in Landscape Architecture and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design. Gwen has practiced landscape architecture as an associate at Studio Outside Landscape Architecture in Dallas, Texas and as a landscape designer at Spackman, Mossop, Michaels in New Orleans, Louisiana. Her design work and research considers kinship to the ground, stories of municipal maintenance, and ways of reading the landscape. Each of these threads are deeply concerned with place, perception, materiality, joy, and whimsy.

The Stories of Maintainers

Our municipal streets and sidewalks are often paved with asphalt and concrete. These continuous surfaces provide a relatively smooth and predictable place for walking: each step follows the previous and the surface of the ground disappears into the ordinary. Without having to carefully navigate over cobblestones or potholes, we can easily forget that our streets and sidewalks are designed, built, and maintained.1 We can forget the fact that their existence requires care—even concrete doesn’t last forever. But if we pay attention, the actions of our cities’ maintainers reveal the complex world below our feet. If we pay attention, we can read the histories of maintenance that keep our streets and sidewalks functioning—in the realm of the invisible and the ordinary.

When considering our perception of the environment while walking along a street, anthropologist Tim Ingold states: “(i)t appears that people, in their daily lives, merely skim the surface of a world that has been previously mapped out and constructed for them to occupy, rather than contributing through their movements to its ongoing formation. To inhabit the modern city is to dwell in an environment that is already built.”2 The following series of photographs acknowledges that our communities are built and persistently maintained by individuals, who are often unrecognized, but who leave their individual mark on the surfaces of our streets—those who are crucial to the “ongoing formation” of our cities.

In an incredibly legible way, the spray paint marks created by utility locators reveal hidden infrastructure to those who notice. The American Public Works Association has developed a uniform color code for temporarily marking utility lines.3 Here, the green paint indicates sewer lines below the asphalt. The arrows indicate the direction of flow, and while walking along the street, one can begin to trace the sewer system as each utility cover is marked with an arrow to indicate subterranean connections.

For each home football game at Auburn University, hundreds of tailgating tents are installed throughout campus. About a week before the first game, utility locators mark the ground with spray paint to indicate the location of each pipe and conduit. The paint appears on nearly every lawn across campus, signaling the arrival of the season with its vibrant colors and lingering paint fumes. These utility marks ensure that no tent stakes disrupt the belowground network.

Beyond utility marking, colors on the ground can also indicate the presence of herbicide. Before application, a blue-green pigment is added to the herbicide solution. This pigment washes away in the rain, and is only intended to last long enough for the applicator to note where it has been applied. Before the herbicide takes action, in a last unintentional celebration of life the color briefly brings attention to these unwanted plants before they die.

Cracks develop in our asphalt streets as the ground shifts and above-ground forces weaken the surface. To repair these cracks, maintainers trace them with asphalt crack filler. In the application of this filler, the patterning of the cracks is revealed, while the personal style of the maintainer also becomes evident. From precise applications to broad “brush strokes” that seem to dance from one crack to another, the asphalt crack filler becomes a paintbrush in the hands of the maintainers. While the presence of the asphalt crack filler might signal degradation to some, it can also be perceived and celebrated as an act of care for our built environment.

Sometimes to maintain our landscape, subtraction is required instead of addition. When concrete cracks and lifts, a grinder can be used to remove protrusions to form a continuous surface again. This act of removing a portion of the lifted concrete reveals its internal structure — often the aggregate — and contrasts with the finished surface of the surrounding concrete. This contrasting band reveals the history of movement and the history of maintenance. One might consider this an indication of what was broken, but one might also see it as a necessary act of care for our landscape. These marks reveal that nothing is static, our landscape—even the paved surfaces—is always evolving.

When simple grinding or patching of the surface isn’t enough, entire areas of concrete are often removed and repoured. Rarely is there an effort to match the color or aggregate of the adjacent concrete. The replacement concrete is often mixed from (and therefore, records) the most readily available sand and aggregate from the time it was poured. Its surface texture is then determined by the installer, who applies their preferred approach to achieve either a broom or trowel finish. For a while, the replacement concrete appears distinctively different from the concrete adjacent to it. It reveals an act of maintenance and records the hands of its installer.

Each of these moments of maintenance and marking exists in the ordinary. “For it is surely through our feet, in contact with the ground, that we are most fundamentally and continually ‘in touch’ with our surroundings.”4 By choosing to walk, and choosing to observe, we engage with the world. Each of these photographs captures a moment of noticing.5 Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing considers human-disturbed landscapes to be ideal places for “noticing.” And in itself, “disturbance is ordinary.”6

Gwendolyn Cohen is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Auburn University. She graduated from the University of Virginia with a Master in Landscape Architecture and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design. Gwen has practiced landscape architecture as an associate at Studio Outside Landscape Architecture in Dallas, Texas and as a landscape designer at Spackman, Mossop, Michaels in New Orleans, Louisiana. Her design work and research considers kinship to the ground, stories of municipal maintenance, and ways of reading the landscape. Each of these threads are deeply concerned with place, perception, materiality, joy, and whimsy.

<-