1 Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 50-72.

2 Redd, Lakewood, CA, Postwar Suburbia in the 21st Century

3 Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier, 50-72.

4 D.J. Waldie, Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 49.

5 Michael Pollan, “Beyond Wilderness and Lawn,” Harvard Design Magazine 5, (1998)

Kate Bilyk

![Figure 1: Photograph of Huntington House, Alisa Bilyk, 2020]()

More often than not, a city is characterized by the way people live in it, with individual dwellings physically embodying their lifestyles. In the United States, the majority of cities cannot be explained or fully understood without acknowledging the development of sparse residential urban form, which constitutes one of the most ordinary built spaces in the country. The suburban single-family house on a subdivided piece of land continues to hold the epitome of middle-class housing and remains one of the most visible and understood goals for ordinary families, as well as an investment opportunity for many to this day. As Walt Whitman once said, “A man is not a whole and complete man, unless he owns a house and the ground it stands on.”1

Suburbia exploded in the post-WWII period, during which new families were formed that gave rise to the baby boom generation, putting an enormous pressure on the housing market. The solution of a mass-produced single-family house built around the values of “economic prosperity, family togetherness, ownership, and a leisure lifestyle” hit the right note, so a new consumer class was formed, composed of “ideal citizens” in the form of working married men and children-raising wives, looking for a place to call home.2

The “suburban dream” framed the house as the centerpiece of a manicured lawn or picturesque English garden surrounded by vast open space and became an idealized place to be as a family. It was almost like a New England village with Thomas Jefferson’s gentleman farmer, creating a new image of the city as an urban-rural continuum. The isolated household became the American middle-class ideal, with the private house representing stability. Suburbia, soaked in sunlight and fresh air, offered an exciting vision that disorder and chaos could be left far away in the decaying metropolis, while the proximity to shopping or entertainment could be maintained. It promised an environment that would combine the best of both city and rural life.3

In 1951, a suburban subdivision’s sales manager said, “We sell happiness in homes.”4

![Photographs of Huntington House, Alisa Bilyk, 2021]()

To this day, most life in America happens in a model home in a model neighborhood in a model landscape, quietly, familiarly, and ordinarily. As someone who grew up in a Northern California model home, I know it well. While not every place has a trace of a particular movement or intervention that we learn about in architecture schools, every place is built upon the idea of a home, a model one or not. The majority of American dwellings are not commissioned by patrons of architectural art and the building market has made customization out of reach for many, while the majority of construction workforce does not specialize in building craftsmanship. Many architectural graduates flock to major metropolitan centers in search of opportunities to build “something special” because that is where culture and those who appreciate architecture reside. But what about everywhere else? What about returning to work in the depths of suburbs far away from the modernist jewels? What about working with typical products, without precious materials, details, or special clients? What about working to strengthen the ordinary, or the staple of American domesticity? The construction of mundane spaces in the United States lacks the attention of architects, and there remains a significant gap between cultural centers and the “rest of the country”. Today, all of us are navigating a myriad of global and regional issues, from climate change to social transformations, or simply, a world that is changing. Therefore, the concern here is not with aesthetics and stylistic solutions in the suburbs, but rather with primal approaches to the way everyday architecture still gets built.

It is clear that there is an overwhelming need for altered zoning laws, that education on built space should be expanded to everyone, and that monopolies on standardization in the building industry need to be reduced. However, the actual resolution of such is a large-scale process and requires extensive efforts. It is true that the job is not easy, but as architects, we can still trigger progress by making small pushes. Such was the attempt in the design of the Huntington House, located in the suburbs of Northern California. Developed without a client, but rather with the idea of mass-appeal, the project was designed to be both familiar to all and to expand established suburban notions of a home. The lack of sophisticated craft available and the limited budget led to the use of simple architectural maneuvers, ordinary construction methods and mostly off-the-shelf products and materials. It may be a house without complex architectural details, but one hopefully with impact.

The approach to Huntington House asks the question of what suburbia could look like if we simply begin to follow a different set of rules.

![Figure 3: Diagrammatic sketch of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 4: Diagrammatic sketch of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 5A: Diagrammatic sketch of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 5B: Diagrammatic sketch of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

Point 1: Minimizing land disruption and maximizing preservation of existing site conditions.

No export or import of soil.

Huntington House was designed with especial consideration for its site. The long, bar-like form preserves the beautiful old oak trees and leaves as much land undisturbed as possible. The excavated soil was redistributed to balance the slope of the site, allowing both the top and lower levels to remain close to grade.

Point 2 : Minimizing foundation mass.

Save concrete, live better.

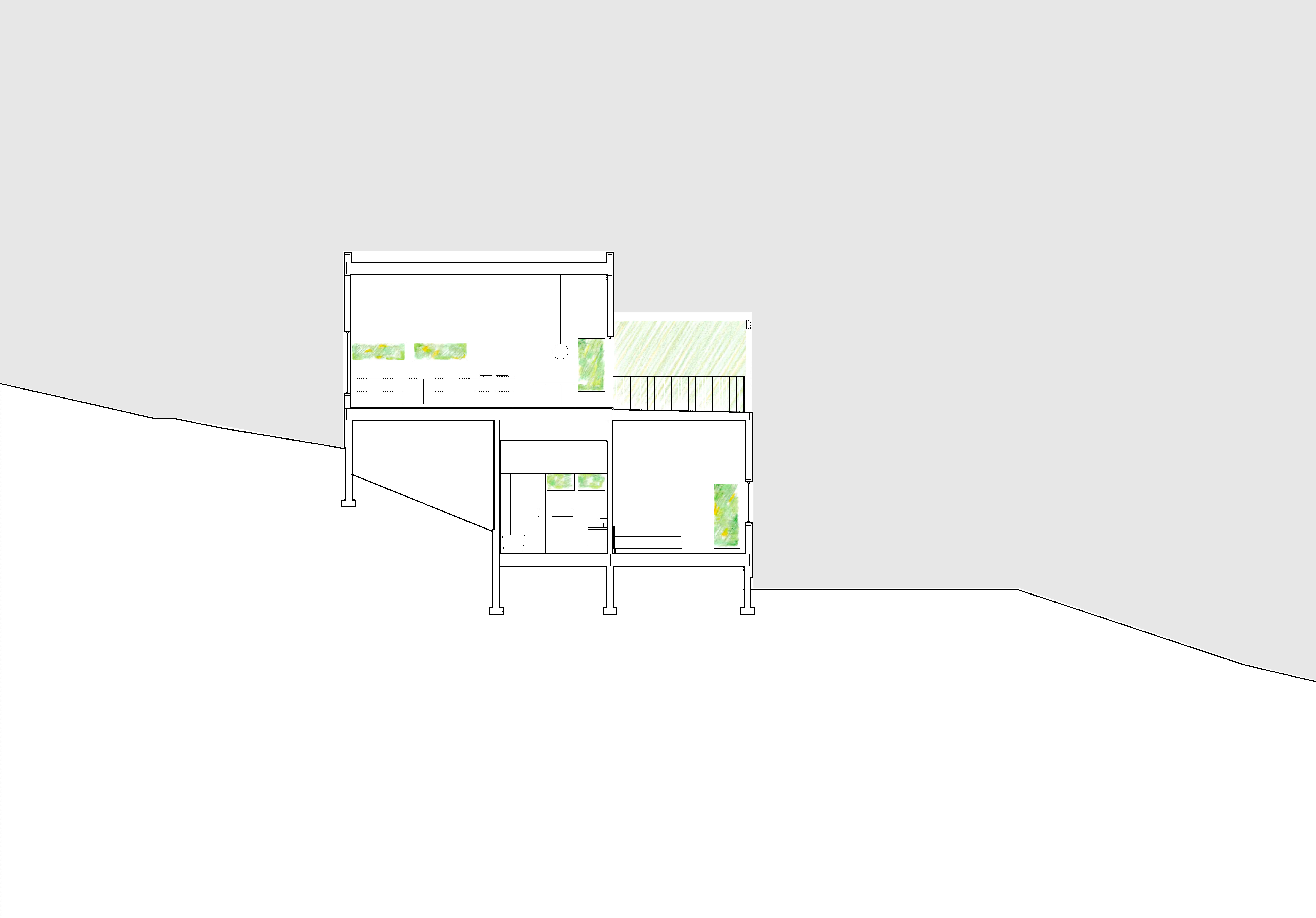

In the context of Northern California, less concrete means less cost. Therefore, avoiding its use as much as possible is the soundest solution, given that concrete construction remains problematic and brings higher costs. Even though the building volume is quite large due to the surrounding context and the provided building size regulations of the neighborhood, simply dividing the building into two narrow rectangular volumes allows for a smaller foundation footprint with only one large retaining wall in the middle of the building. Consequently, the building is lighter and more flexible (Figure 4).

Point 3 : Using readily available materials efficiently.

![Figure 6: Photographs of Huntington House by Alisa Bilyk, 2020.]()

Buy local.

The stick-frame timber construction enabled rapid growth of the first suburban neighborhoods, making it possible to sell tens of houses per day in some places. The light timber frame remains to be the most common method of residential construction. It is economical, efficient, and sustainable, since timber can be viewed as a regenerative material. However, construction still generates a lot of material waste, so the house was designed to fit standard material lengths, limiting building spans and simplifying overall framing (Figure 5).

Point 4 : Utilizing roof surfaces for programs, solar panels, gardens, etc.

![Figure 8: Drawing of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 7: Photograph of Huntington House by Alisa Bilyk, 2021.]()

No roof wasted.

To pursue efficiency, the usable areas of the house are maximized, and the roof space is never wasted. Roofs are designed to accommodate the addition of solar panels, gardens, and even terraces. The lower-level roof is transformed into a grand terrace for the main level of the house. The terrace can be imagined almost as an outdoor living room, with its northern end comfortably surrounded by trees and protected by a pergola, while its southern end dramatically opens to the site. A third small terrace on the roof of the main entrance to the house offers a cozy nook. Screened from the street, only allowing for a small peak towards the lake, it opens to the back of the site with an expansive view on the surrounding El Dorado Hills (Figures 7 & 8).

Point 5 : Maximizing connection to the outdoors in order to promote engagement with exterior space.

Always a way out.

With the exception of the guest suite and utility spaces such as bathrooms and storage, every room in the house has access to the outdoors. The lower level was brought close to grade to invite the house inhabitants to engage with the landscape and blur the boundary between the indoor and outdoor space. The front porch provides a public space that engages with the neighborhood, while access to the terrace from the living area and kitchen are based on California climate that allows for all indoor activities to take place outside for the majority of the year. In that sense, habitat in a house is viewed as space without a break from the outdoors (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

![Figure 9: Ground Floor Plan of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 10: Lower Floor Plan of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

Point 6: Organizing the house to work with passive climatic conditions for energy use reduction.

Form follows sun.

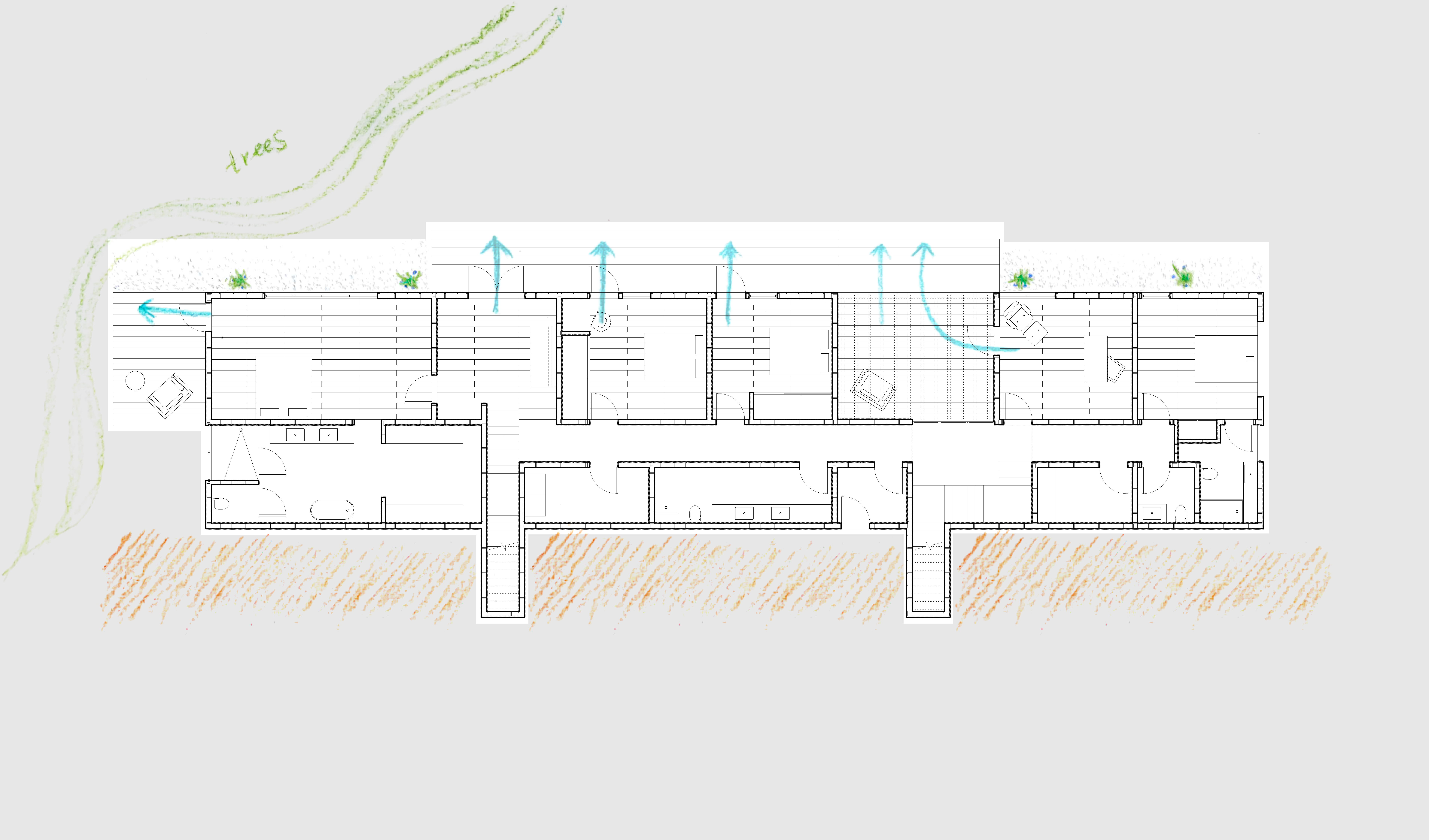

Most of the openings in the house face East, including the garden and all the terraces. Therefore, the majority of the house is bathed in morning and early afternoon light and breeze, while the heat of the afternoons will fall onto the short end (the least inhabited part of the house) where the garage is located. During sunset, the soft pink glow enters the living room through large windows, adding a sparkle to the fireplace. The summer heat of Northern California can be brutal, especially as temperatures are crawling higher for longer every year, which leads to increased use of air-conditioning. The house reduces the heat impact through the overwhelming east exposure of the house, the preservation of almost all existing oak trees on site, and the decision to face the short end of the volume towards the south and southwest. Similarly, the earth mass that is sandwiched between the two levels due to their sectional offset helps to cool the house. Many operable doors and windows allow for cross-ventilation, thereby dramatically reducing the use of air conditioning (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

Point 7 : Providing a variety of interior and exterior spaces to promote relationships between the body, building as shell, and the environment.

![Figure 12D: Section Drawings of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2022.]()

![Figure 11: Photographs of Huntington House by Alisa Bilyk, 2021.]()

![Figure 12C: Section Drawings of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2022.]()

![Figure 12B: Section Drawings of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2022.]()

![Figure 12A: Section Drawings of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2022.]()

A house is a world-viewing device.

Interior space was planned to offer spatial variety and provide a functional living. The house is organized into a public main level and a more private lower level. Unlike a simple long bar for the lower level, the main level is a collection of differently sized volumes. One of the main spaces on this floor is the living room, which is the tallest and most spacious room in the house and a public hearth that connects to the terrace that opens to an expansive view of the hills. Beyond the living room, a secluded kitchen serves as a private hearth where ordinary activities unfold. Just like the living room, the kitchen is also connected to the terrace, but in this case, to the cozy tree-covered side, which can easily transform into an outdoor breakfast room. The two levels are connected by two staircases, which further divide the lower level into two zones: a private zone and a work/guest zone. The private zone is organized around a common room, which acts as the center of the wing and can take on many functions – a playroom for children, a small library, a craft studio, etc. On the opposite side of the house is the work/guest zone, which is directly accessible from the main level through the second staircase. The proximity to the house entrance allows for the office space to potentially receive external visitors or provides an easy route for bringing supplies from the garage. While the southern wing has been zoned differently than the northern living wing, flexibility remains very important. Therefore, both the office and the guest suite can be easily transformed into additional bedrooms or all bedrooms can take on different functions. This allows for the lower private level to act as a series of compartments that are easily adaptable, while the changing roof line makes the top level much more function-specific. Even the garage has been organized in such a way that the smaller portion can be transformed into a bedroom with an access to the house and the terrace at the back, while the back wall can be punctured to bring in a view to the back yard. The double orientation of the living room and the triple orientation of the kitchen give the house a sense of porosity, connecting it to both the garden in the back and the neighborhood through the front yard. The project’s ambition lies in the idea that a dwelling should provide spaces for introversion, connection to landscape, areas for communal informal exchange, but also that it should extend itself into the public domain (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

![Figure 13: Drawing of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2023.]()

![Figure 14: Photograph of Huntington House by Kate Bilyk, 2021.]()

P.S. Landscape:

The front and back yards are inseparable parts of a suburban house and are more like components defined by zoning regulations, than an overarching landscape. It is common that the backyard is legislated to be smaller than the front yard, fenced off as privatized outdoor space. Huntington House is no exception; however, unlike other brand-new subdivision developments, the backyard preserves existing plants and a number of old oak trees. Except for the grade adjustment at the face of the house, the majority of topography and rock was preserved in the back, maintaining an as-it-was condition prior to construction.

The front yard, on the other hand, has held significance in the American housing story. Before the 1860s, it was not common to have a front yard at all. It was gradually elevated from a patch of grass into an expression of society by advocating for a smooth, well-maintained green surface as an essential element of beauty in a suburban home. It was established that one’s lawn should contribute to the prosperous collective landscape and to express like-mindedness with its neighbors. Therefore, maintenance of the lawn has become a civic obligation, as most regard the front lawns as belonging to the community, while the backyards belong exclusively to the homeowners.5

However, in California, with its burning sunshine during the better part of the year, the maintenance of a perfect lawn costs gallons of water, which are becoming increasingly scarce. Shall civic duty come at the cost of the natural environment? What is the more patriotic choice – pretending to have a year-round green lawn or preserving water? At Huntington House, we believe that preserving water is the civic duty. The house was placed at the line of the allowable zone for construction, taking the minimal area for the front yard, and considering the south-west orientation of the front yard, no lawn has been instituted to preserve water and maintenance. Rather, the front landscape consists of local sand and rock compositions, paying homage to the rocky soil of the area and remains beautifully timeless (Figures 13, 14 & 15).

![Figure 16: Photograph of Huntington House by Alisa Bilyk; 2020.]()

![Figure 15: Photographs of Huntington House by Alisa Bilyk; 2021.]()

P.S.S. Last thoughts:

As suburbia has taken on the role of representing American domesticity, it became a physical embodiment of the society it houses. The way a particular community builds itself carries an inherent expression about its values and it is precisely when architecture tells us something about ourselves and the world we live in that it begins to matter. If one is to assume that there is an inherent voice in each building that must be exercised, then what do we talk about? If architecture is inevitable, as buildings are part of everyday life, and if the majority of the built fabric is mundane, isn’t it precisely there that we should lobby for implementing change? If architecture is, more often than not, a response to its context, be it physical, political, social, or economic, then how it does so weighs the most. Therefore, we should design and build in a way that promotes responsible land management, symbiotic living with natural environment, preservation of resources, social diversity, connection to community, and much more. We should continue to question the suburban building typologies, zoning and building codes, and development processes. Furthermore, we should foster an active discourse about the built environment with the community-at-large and cultivate curiosity and understanding in the way we build our world.

Kate Bilyk is an architectural designer, researcher and educator based in Berlin and California. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture from California Polytechnic University, Pomona, and a Master of Architecture from Princeton University. She has previously worked at such offices as Johnston Marklee and Barkow Leibinger and taught at the Technical University of Berlin. Her own work focuses on expanding the discipline of architecture towards wider audiences and contexts.

Returning to the Neighborhood

More often than not, a city is characterized by the way people live in it, with individual dwellings physically embodying their lifestyles. In the United States, the majority of cities cannot be explained or fully understood without acknowledging the development of sparse residential urban form, which constitutes one of the most ordinary built spaces in the country. The suburban single-family house on a subdivided piece of land continues to hold the epitome of middle-class housing and remains one of the most visible and understood goals for ordinary families, as well as an investment opportunity for many to this day. As Walt Whitman once said, “A man is not a whole and complete man, unless he owns a house and the ground it stands on.”1

Suburbia exploded in the post-WWII period, during which new families were formed that gave rise to the baby boom generation, putting an enormous pressure on the housing market. The solution of a mass-produced single-family house built around the values of “economic prosperity, family togetherness, ownership, and a leisure lifestyle” hit the right note, so a new consumer class was formed, composed of “ideal citizens” in the form of working married men and children-raising wives, looking for a place to call home.2

The “suburban dream” framed the house as the centerpiece of a manicured lawn or picturesque English garden surrounded by vast open space and became an idealized place to be as a family. It was almost like a New England village with Thomas Jefferson’s gentleman farmer, creating a new image of the city as an urban-rural continuum. The isolated household became the American middle-class ideal, with the private house representing stability. Suburbia, soaked in sunlight and fresh air, offered an exciting vision that disorder and chaos could be left far away in the decaying metropolis, while the proximity to shopping or entertainment could be maintained. It promised an environment that would combine the best of both city and rural life.3

In 1951, a suburban subdivision’s sales manager said, “We sell happiness in homes.”4

To this day, most life in America happens in a model home in a model neighborhood in a model landscape, quietly, familiarly, and ordinarily. As someone who grew up in a Northern California model home, I know it well. While not every place has a trace of a particular movement or intervention that we learn about in architecture schools, every place is built upon the idea of a home, a model one or not. The majority of American dwellings are not commissioned by patrons of architectural art and the building market has made customization out of reach for many, while the majority of construction workforce does not specialize in building craftsmanship. Many architectural graduates flock to major metropolitan centers in search of opportunities to build “something special” because that is where culture and those who appreciate architecture reside. But what about everywhere else? What about returning to work in the depths of suburbs far away from the modernist jewels? What about working with typical products, without precious materials, details, or special clients? What about working to strengthen the ordinary, or the staple of American domesticity? The construction of mundane spaces in the United States lacks the attention of architects, and there remains a significant gap between cultural centers and the “rest of the country”. Today, all of us are navigating a myriad of global and regional issues, from climate change to social transformations, or simply, a world that is changing. Therefore, the concern here is not with aesthetics and stylistic solutions in the suburbs, but rather with primal approaches to the way everyday architecture still gets built.

It is clear that there is an overwhelming need for altered zoning laws, that education on built space should be expanded to everyone, and that monopolies on standardization in the building industry need to be reduced. However, the actual resolution of such is a large-scale process and requires extensive efforts. It is true that the job is not easy, but as architects, we can still trigger progress by making small pushes. Such was the attempt in the design of the Huntington House, located in the suburbs of Northern California. Developed without a client, but rather with the idea of mass-appeal, the project was designed to be both familiar to all and to expand established suburban notions of a home. The lack of sophisticated craft available and the limited budget led to the use of simple architectural maneuvers, ordinary construction methods and mostly off-the-shelf products and materials. It may be a house without complex architectural details, but one hopefully with impact.

The approach to Huntington House asks the question of what suburbia could look like if we simply begin to follow a different set of rules.

Point 1: Minimizing land disruption and maximizing preservation of existing site conditions.

No export or import of soil.

Huntington House was designed with especial consideration for its site. The long, bar-like form preserves the beautiful old oak trees and leaves as much land undisturbed as possible. The excavated soil was redistributed to balance the slope of the site, allowing both the top and lower levels to remain close to grade.

Point 2 : Minimizing foundation mass.

Save concrete, live better.

In the context of Northern California, less concrete means less cost. Therefore, avoiding its use as much as possible is the soundest solution, given that concrete construction remains problematic and brings higher costs. Even though the building volume is quite large due to the surrounding context and the provided building size regulations of the neighborhood, simply dividing the building into two narrow rectangular volumes allows for a smaller foundation footprint with only one large retaining wall in the middle of the building. Consequently, the building is lighter and more flexible (Figure 4).

Point 3 : Using readily available materials efficiently.

Buy local.

The stick-frame timber construction enabled rapid growth of the first suburban neighborhoods, making it possible to sell tens of houses per day in some places. The light timber frame remains to be the most common method of residential construction. It is economical, efficient, and sustainable, since timber can be viewed as a regenerative material. However, construction still generates a lot of material waste, so the house was designed to fit standard material lengths, limiting building spans and simplifying overall framing (Figure 5).

Point 4 : Utilizing roof surfaces for programs, solar panels, gardens, etc.

No roof wasted.

To pursue efficiency, the usable areas of the house are maximized, and the roof space is never wasted. Roofs are designed to accommodate the addition of solar panels, gardens, and even terraces. The lower-level roof is transformed into a grand terrace for the main level of the house. The terrace can be imagined almost as an outdoor living room, with its northern end comfortably surrounded by trees and protected by a pergola, while its southern end dramatically opens to the site. A third small terrace on the roof of the main entrance to the house offers a cozy nook. Screened from the street, only allowing for a small peak towards the lake, it opens to the back of the site with an expansive view on the surrounding El Dorado Hills (Figures 7 & 8).

Point 5 : Maximizing connection to the outdoors in order to promote engagement with exterior space.

Always a way out.

With the exception of the guest suite and utility spaces such as bathrooms and storage, every room in the house has access to the outdoors. The lower level was brought close to grade to invite the house inhabitants to engage with the landscape and blur the boundary between the indoor and outdoor space. The front porch provides a public space that engages with the neighborhood, while access to the terrace from the living area and kitchen are based on California climate that allows for all indoor activities to take place outside for the majority of the year. In that sense, habitat in a house is viewed as space without a break from the outdoors (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

Point 6: Organizing the house to work with passive climatic conditions for energy use reduction.

Form follows sun.

Most of the openings in the house face East, including the garden and all the terraces. Therefore, the majority of the house is bathed in morning and early afternoon light and breeze, while the heat of the afternoons will fall onto the short end (the least inhabited part of the house) where the garage is located. During sunset, the soft pink glow enters the living room through large windows, adding a sparkle to the fireplace. The summer heat of Northern California can be brutal, especially as temperatures are crawling higher for longer every year, which leads to increased use of air-conditioning. The house reduces the heat impact through the overwhelming east exposure of the house, the preservation of almost all existing oak trees on site, and the decision to face the short end of the volume towards the south and southwest. Similarly, the earth mass that is sandwiched between the two levels due to their sectional offset helps to cool the house. Many operable doors and windows allow for cross-ventilation, thereby dramatically reducing the use of air conditioning (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

Point 7 : Providing a variety of interior and exterior spaces to promote relationships between the body, building as shell, and the environment.

A house is a world-viewing device.

Interior space was planned to offer spatial variety and provide a functional living. The house is organized into a public main level and a more private lower level. Unlike a simple long bar for the lower level, the main level is a collection of differently sized volumes. One of the main spaces on this floor is the living room, which is the tallest and most spacious room in the house and a public hearth that connects to the terrace that opens to an expansive view of the hills. Beyond the living room, a secluded kitchen serves as a private hearth where ordinary activities unfold. Just like the living room, the kitchen is also connected to the terrace, but in this case, to the cozy tree-covered side, which can easily transform into an outdoor breakfast room. The two levels are connected by two staircases, which further divide the lower level into two zones: a private zone and a work/guest zone. The private zone is organized around a common room, which acts as the center of the wing and can take on many functions – a playroom for children, a small library, a craft studio, etc. On the opposite side of the house is the work/guest zone, which is directly accessible from the main level through the second staircase. The proximity to the house entrance allows for the office space to potentially receive external visitors or provides an easy route for bringing supplies from the garage. While the southern wing has been zoned differently than the northern living wing, flexibility remains very important. Therefore, both the office and the guest suite can be easily transformed into additional bedrooms or all bedrooms can take on different functions. This allows for the lower private level to act as a series of compartments that are easily adaptable, while the changing roof line makes the top level much more function-specific. Even the garage has been organized in such a way that the smaller portion can be transformed into a bedroom with an access to the house and the terrace at the back, while the back wall can be punctured to bring in a view to the back yard. The double orientation of the living room and the triple orientation of the kitchen give the house a sense of porosity, connecting it to both the garden in the back and the neighborhood through the front yard. The project’s ambition lies in the idea that a dwelling should provide spaces for introversion, connection to landscape, areas for communal informal exchange, but also that it should extend itself into the public domain (Figures 9, 10 & 12).

P.S. Landscape:

The front and back yards are inseparable parts of a suburban house and are more like components defined by zoning regulations, than an overarching landscape. It is common that the backyard is legislated to be smaller than the front yard, fenced off as privatized outdoor space. Huntington House is no exception; however, unlike other brand-new subdivision developments, the backyard preserves existing plants and a number of old oak trees. Except for the grade adjustment at the face of the house, the majority of topography and rock was preserved in the back, maintaining an as-it-was condition prior to construction.

The front yard, on the other hand, has held significance in the American housing story. Before the 1860s, it was not common to have a front yard at all. It was gradually elevated from a patch of grass into an expression of society by advocating for a smooth, well-maintained green surface as an essential element of beauty in a suburban home. It was established that one’s lawn should contribute to the prosperous collective landscape and to express like-mindedness with its neighbors. Therefore, maintenance of the lawn has become a civic obligation, as most regard the front lawns as belonging to the community, while the backyards belong exclusively to the homeowners.5

However, in California, with its burning sunshine during the better part of the year, the maintenance of a perfect lawn costs gallons of water, which are becoming increasingly scarce. Shall civic duty come at the cost of the natural environment? What is the more patriotic choice – pretending to have a year-round green lawn or preserving water? At Huntington House, we believe that preserving water is the civic duty. The house was placed at the line of the allowable zone for construction, taking the minimal area for the front yard, and considering the south-west orientation of the front yard, no lawn has been instituted to preserve water and maintenance. Rather, the front landscape consists of local sand and rock compositions, paying homage to the rocky soil of the area and remains beautifully timeless (Figures 13, 14 & 15).

P.S.S. Last thoughts:

As suburbia has taken on the role of representing American domesticity, it became a physical embodiment of the society it houses. The way a particular community builds itself carries an inherent expression about its values and it is precisely when architecture tells us something about ourselves and the world we live in that it begins to matter. If one is to assume that there is an inherent voice in each building that must be exercised, then what do we talk about? If architecture is inevitable, as buildings are part of everyday life, and if the majority of the built fabric is mundane, isn’t it precisely there that we should lobby for implementing change? If architecture is, more often than not, a response to its context, be it physical, political, social, or economic, then how it does so weighs the most. Therefore, we should design and build in a way that promotes responsible land management, symbiotic living with natural environment, preservation of resources, social diversity, connection to community, and much more. We should continue to question the suburban building typologies, zoning and building codes, and development processes. Furthermore, we should foster an active discourse about the built environment with the community-at-large and cultivate curiosity and understanding in the way we build our world.

Kate Bilyk is an architectural designer, researcher and educator based in Berlin and California. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture from California Polytechnic University, Pomona, and a Master of Architecture from Princeton University. She has previously worked at such offices as Johnston Marklee and Barkow Leibinger and taught at the Technical University of Berlin. Her own work focuses on expanding the discipline of architecture towards wider audiences and contexts.

<-