Kelly Hendriks /B-ILD

We intend to put forward some reflections on the tension between the ordinary and the exceptional through the reading of the Smithsons’ Hunstanton School, which served as a major reference during the design process of our own recently realized Warot Building. By looking at these two projects, we hope to exemplify how in the context of public commissions, the use of ordinary craftsmanship can be used as leverage to achieve exceptional results.

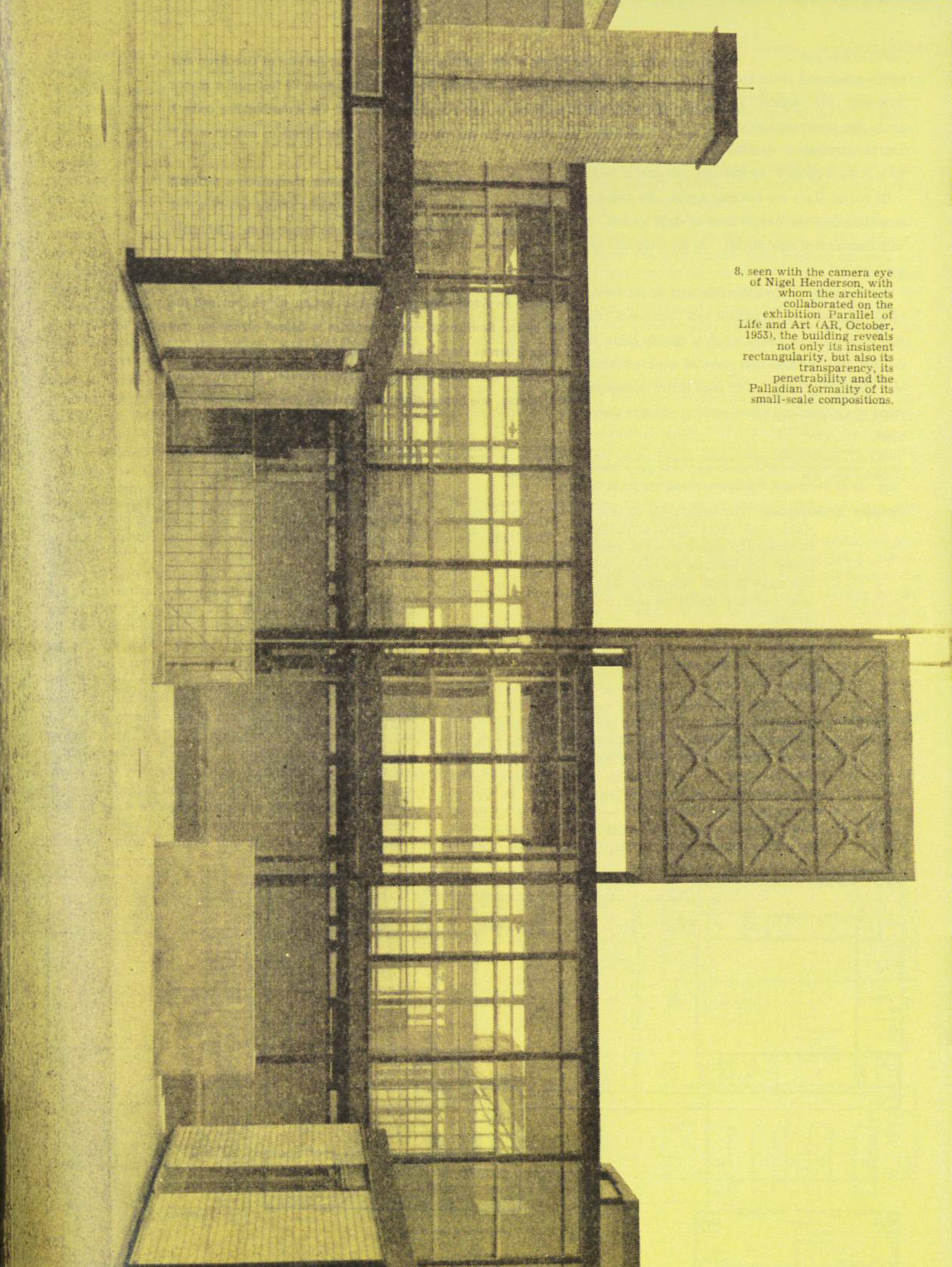

![School at Hunstanton under construction, Alison and Peter Smithson, UK, ca. 1954 (credits unknown)]()

![Warot Building, B-ILD, Belgium, 2020 (Image by Jeroen Verrecht)]()

In the Smithsons’ Hunstanton school, everyday materials are deployed in (at the time) unconventional ways and recontextualized by design to form an architectural statement. This school, certainly in its time, could hardly be called ordinary, yet its material means are radically common and standardized. The building not only exposes its structure but also incorporates as-found technical elements such as boilers, ducts, electrical wires, and other infrastructural parts into a new and radical esthtical language. By applying industrial architectural concepts (the ordinary) to a non-industrial program, these building components challenge design conventions while still succeeding in creating “the exceptional”: more school for less budget. Equally as important, they prove that this unconventional way of thinking does not result in an inferior building. As such, the exceptional is made possible by the ordinary while the ordinary is revealed by the exceptional.

In our own work, we perceive this dichotomy of ordinary and exceptional not as a stylistic concept but as an incentive to answer socio-economic questions, which we are often confronted with in project and competition briefs. We think of two of these socio-economic topics that are close to our hearts and can be linked to this topic of the ordinary: craftsmanship and inclusivity.

![Warot Building, Belgium, B-ILD, 2020 (Image by Jeroen Verrecht)]()

![School at Hunstanton, Alison and Peter Smithson, UK, ca. 1954 (Image by Reginald Hugo de Bugh Galwey, all rights to RIBA)]()

Our interest in creating added socio-economic value has led us to primarily take up projects for the public sector, where we are always looking for ways to do as much as possible with the modest budgets at hand. It is in this challenge that lies our craftsmanship. Rather than seeing craftsmanship as something artisanal, small-scale, or closely linked to making, we understand our craftsmanship as the achievement of a detailed understanding of the process through which buildings come to be. We found that common materials, standard measurements, and generic details are great allies in this endeavor. Being exceptional in a technical or flashy way is of much lesser importance to our work than setting ambitious goals of generosity, sustainability, economy, and inclusivity.

Nowadays, architects must consider an increasing amount of factors. Many of these factors become technical and energetic demands under the law, client’s request, or result in industrial modes of making. It is increasingly important to work closely together with engineers, consultants, users, and contractors. As architecture focuses more on these collaborations, the architect’s craftsmanship shifts towards navigating the construction process in a way that the end result can be built, considering an increasingly restrictive amount of conflicting requirements. The use of standard solutions and inclusion of as-found elements thus become tools for inclusion of and communication with these other actors. The ordinary can then be identified as the common language that allows for mediation between structural and acoustic engineers, (sub-)contractors, subsidizing authorities, facility managers, technical engineers, energy advisors, clients, end users, and us, architects. The compilation of normative requirements, building codes, development of materials, and construction methods create a kind of building culture, almost like an evolving vernacular language, that we consider as the common ground for bringing different actors to the table.

By applying standard solutions without unnecessarily complicating the design, all parties involved can easily understand their requirements, where they can contribute their authorship, and how to achieve the shared goal of providing as much space as possible with the modest means available. This way, not only the resultant space itself aims to be inclusive, but also the building process allows for a wider range of opinions and concerns to more organically inform and develop the project. Our working method hopes to result in projects that anyone can understand and, perhaps just as importantly, anyone can execute.

![Warot Building, Belgium, B-ILD, 2020 (Image by Jeroen Verrecht)]()

![School at Hunstanton, Alison and Peter Smithson, UK, ca. 1954 (Image by Reginald Hugo de Bugh Galwey, all rights to RIBA)]()

The Warot building exemplifies this exploration of inclusive craftsmanship as it aims to be truly embedded and used by the community for the long term. This increased the complexity of our design by involving as many local actors as possible and seeking to do the most with the limited means available. “More space for less budget” became the priority and we decided to strategically invest the available funds where most impact would be in: space, adaptability, and structure.

The resulting building is a small multifunctional hall in an ordinary Belgian village. The new volume is positioned at the center of a number of public sports facilities and designed as a space for a variety of activities ranging from children's play and card games to yoga classes. The lower volume’s simple, symmetrical floor plan offers a base for these activities. The plan follows a structure of six parallel beams, generating spaces that can be interconnected or partitioned through the use of folding walls. These rooms are serviced by a wide corridor that provides a backstage and contains circulation, storage, and technical functions. A wide glazed bay faces a playing field across a small stream, its sliding doors opening up to a covered exterior space that extends the interior space. With these tools, the multipurpose hall offers an open infrastructure to the community where partition walls can be rearranged and circulations can be multiplied to accommodate a wide range of activities. These non-loadbearing walls enable future adaptability as the village’s needs evolve. This emphasis on adaptability produces a truly inclusive project and enables the building to remain meaningful for generations to come.

![Warot Building, Belgium, B-ILD, 2020 (Image by Jeroen Verrecht)]()

![School at Hunstanton, Alison and Peter Smithson, UK, ca. 1954 (Image rights to the Smithsons family collection)]()

Considering the modest budget, common materials were strategically chosen for simplicity, their ease of construction, durability, and ease of maintenance while assuring a low ecological impact. The roof structure consists of steel beams that support a sheet of perforated corrugated steel. The choice to perforate and expose this structural sheet of steel ensures the acoustic quality inside the building while avoiding the cost of expensive acoustic finishing.

Looking at the Warot building, the paradox between the ordinary and the exceptional lies in the search to achieve maximum (inclusivity) with the minimum necessary (craftsmanship). We strategically center the design and building process around common denominators such as industrial materials and standard detailing, allowing a kind of contemporary vernacular to inform the project. The resulting building is, despite being composed of ordinary elements, offers an unhoped amount of space. Our hope is the daily use of space and the architecture itself serves as an unassuming stage for a wide range of activities.

B-ILD is an architecture studio established in Brussels, Belgium in 2009. Their projects are diverse in scale and program. The work of B-ILD is based on their search for layered simplicity in complex environments. A specific working methodology and strategy is created for each type of project.

Common Craftsmanship

We intend to put forward some reflections on the tension between the ordinary and the exceptional through the reading of the Smithsons’ Hunstanton School, which served as a major reference during the design process of our own recently realized Warot Building. By looking at these two projects, we hope to exemplify how in the context of public commissions, the use of ordinary craftsmanship can be used as leverage to achieve exceptional results.

In the Smithsons’ Hunstanton school, everyday materials are deployed in (at the time) unconventional ways and recontextualized by design to form an architectural statement. This school, certainly in its time, could hardly be called ordinary, yet its material means are radically common and standardized. The building not only exposes its structure but also incorporates as-found technical elements such as boilers, ducts, electrical wires, and other infrastructural parts into a new and radical esthtical language. By applying industrial architectural concepts (the ordinary) to a non-industrial program, these building components challenge design conventions while still succeeding in creating “the exceptional”: more school for less budget. Equally as important, they prove that this unconventional way of thinking does not result in an inferior building. As such, the exceptional is made possible by the ordinary while the ordinary is revealed by the exceptional.

In our own work, we perceive this dichotomy of ordinary and exceptional not as a stylistic concept but as an incentive to answer socio-economic questions, which we are often confronted with in project and competition briefs. We think of two of these socio-economic topics that are close to our hearts and can be linked to this topic of the ordinary: craftsmanship and inclusivity.

Our interest in creating added socio-economic value has led us to primarily take up projects for the public sector, where we are always looking for ways to do as much as possible with the modest budgets at hand. It is in this challenge that lies our craftsmanship. Rather than seeing craftsmanship as something artisanal, small-scale, or closely linked to making, we understand our craftsmanship as the achievement of a detailed understanding of the process through which buildings come to be. We found that common materials, standard measurements, and generic details are great allies in this endeavor. Being exceptional in a technical or flashy way is of much lesser importance to our work than setting ambitious goals of generosity, sustainability, economy, and inclusivity.

Nowadays, architects must consider an increasing amount of factors. Many of these factors become technical and energetic demands under the law, client’s request, or result in industrial modes of making. It is increasingly important to work closely together with engineers, consultants, users, and contractors. As architecture focuses more on these collaborations, the architect’s craftsmanship shifts towards navigating the construction process in a way that the end result can be built, considering an increasingly restrictive amount of conflicting requirements. The use of standard solutions and inclusion of as-found elements thus become tools for inclusion of and communication with these other actors. The ordinary can then be identified as the common language that allows for mediation between structural and acoustic engineers, (sub-)contractors, subsidizing authorities, facility managers, technical engineers, energy advisors, clients, end users, and us, architects. The compilation of normative requirements, building codes, development of materials, and construction methods create a kind of building culture, almost like an evolving vernacular language, that we consider as the common ground for bringing different actors to the table.

By applying standard solutions without unnecessarily complicating the design, all parties involved can easily understand their requirements, where they can contribute their authorship, and how to achieve the shared goal of providing as much space as possible with the modest means available. This way, not only the resultant space itself aims to be inclusive, but also the building process allows for a wider range of opinions and concerns to more organically inform and develop the project. Our working method hopes to result in projects that anyone can understand and, perhaps just as importantly, anyone can execute.

The Warot building exemplifies this exploration of inclusive craftsmanship as it aims to be truly embedded and used by the community for the long term. This increased the complexity of our design by involving as many local actors as possible and seeking to do the most with the limited means available. “More space for less budget” became the priority and we decided to strategically invest the available funds where most impact would be in: space, adaptability, and structure.

The resulting building is a small multifunctional hall in an ordinary Belgian village. The new volume is positioned at the center of a number of public sports facilities and designed as a space for a variety of activities ranging from children's play and card games to yoga classes. The lower volume’s simple, symmetrical floor plan offers a base for these activities. The plan follows a structure of six parallel beams, generating spaces that can be interconnected or partitioned through the use of folding walls. These rooms are serviced by a wide corridor that provides a backstage and contains circulation, storage, and technical functions. A wide glazed bay faces a playing field across a small stream, its sliding doors opening up to a covered exterior space that extends the interior space. With these tools, the multipurpose hall offers an open infrastructure to the community where partition walls can be rearranged and circulations can be multiplied to accommodate a wide range of activities. These non-loadbearing walls enable future adaptability as the village’s needs evolve. This emphasis on adaptability produces a truly inclusive project and enables the building to remain meaningful for generations to come.

Considering the modest budget, common materials were strategically chosen for simplicity, their ease of construction, durability, and ease of maintenance while assuring a low ecological impact. The roof structure consists of steel beams that support a sheet of perforated corrugated steel. The choice to perforate and expose this structural sheet of steel ensures the acoustic quality inside the building while avoiding the cost of expensive acoustic finishing.

Looking at the Warot building, the paradox between the ordinary and the exceptional lies in the search to achieve maximum (inclusivity) with the minimum necessary (craftsmanship). We strategically center the design and building process around common denominators such as industrial materials and standard detailing, allowing a kind of contemporary vernacular to inform the project. The resulting building is, despite being composed of ordinary elements, offers an unhoped amount of space. Our hope is the daily use of space and the architecture itself serves as an unassuming stage for a wide range of activities.

B-ILD is an architecture studio established in Brussels, Belgium in 2009. Their projects are diverse in scale and program. The work of B-ILD is based on their search for layered simplicity in complex environments. A specific working methodology and strategy is created for each type of project.

<-