1 For a historical analysis of European architects, who in the beginning of the 20th century, believed that a model for the way modernist architecture should develop could be found in the work of United States industrial buildings, see Reyner Banham, A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture 1900-1925 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986).

2 The German dramatist-poet Bertolt Brecht regarded Viktor Shklovsky’s theory of ostranenie (“making it strange,” or defamiliarization), as a method of helping readers understand the complex nexuses of historical development and societal relationships within a given text. Shklovsky argued that defamiliarization can be achieved through the use of linguistic devices, nonlinear narrative structures, shifts in perspective, and the highlighting of technique itself. By drawing attention to the form and the means of literary production, it was maintained that the reader is prompted to reflect on the process of perception and the construction of meaning. See Victor Shklovsky, "Art as Technique," in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965).

3 For a summary of the argument that the Anthropocene is rooted in specific historical processes associated with industrial capitalism and its expansion across the globe, see Christophe Bonneuil, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, and David Fernbach, The Shock of the Anthropocene the Earth, History and US (London: Verso, 2017).

4 Environmental Protection Agency, Tri-State Mining District – Chat Mining Waste, (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency, 2007).

5 Charles Waldheim and Alan Berger, “Logistics Landscape,” Landscape Journal 27, no. 2 (2008): 219-46, https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.27.2.219.

6 Environmental Protection Agency, Sixth Five-Year Review Report for Cherokee County Superfund Site Cherokee County, Kansas (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency, 2020).

7 Environmental Protection Agency, Review Report for Cherokee County.

8 Sigmund Freud, "The Uncanny," in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud Vol. XVII (1917-1919), trans. James Strachey, ed. Angela Richards (London: The Hogarth Press, 1953), 217–52.

9 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 181.

10 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 248.

11 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 194.

12 Walter Gropius, “Die Entwicklung Moderner Industriebaukunst,” in Mildred Benton, Janetta Rebold Benton, and Robert Sharp, Form and Function: A Guide to Three-Dimensional Design (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1975).

13 Graham Harman’s philosophical framework of subject-object relations revolves around four key components, or quadruple relations, that constitute the structure of reality. First is Real Objects: According to Harman, the world is composed of real objects that exist independently of human perception and cognition. These real objects possess withdrawn and hidden qualities that are inaccessible to direct human experience. Secondly, Sensual objects are the aspects of objects that we perceive and interact with in our everyday experience. These objects are shaped by our sensory and cognitive capacities, and they differ from the real objects that underlie them. Third is Real Qualities, which refer to the withdrawn and hidden aspects of real objects. Harman argues that these qualities cannot be fully known or reduced to their sensual manifestations. Fourth is Sensual Qualities, which are the properties that we perceive in sensual objects. See Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2011).

14 Kant’s epistemology, in particular his insight into how we experience the world, remains foundational to continental philosophy today. He explains that the human world is composed of phenomena, the infinite array of objects and events of human experience. He also states that the world is composed of noumena we cannot experience, the equally infinite number of things that exist, and processes that take place, apart from our minds thinking of them. These two domains remain separate but nonetheless linked, inasmuch as noumena are the basis for phenomena. See Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1998.

15 Andrew Cole. “Those Obscure Objects Of Desire: The Uses And Abuses Of Object-Oriented Ontology And Speculative Realism,” Artforum 53, no. 10, 2015.

16 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1976), 163–64.

17 Cole. “Those Obscure Objects Of Desire,” 11.

18 Helmut Weber, Walter Gropius Und Das Faguswerk (Munich: Verlag G.D.W. Callwey, 1961), 27-28.

19 Barthes maintains that myth is not confined to ancient stories but permeates contemporary society, disguising its ideological nature and perpetuating dominant values. Through his analysis of cultural artifacts, he reveals how myth operates as a system of signs and symbols that shape an understanding of the world and influence social and cultural norms. See Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972).

20 The emergence of technical reason during the Scientific Revolution led to a fundamental shift in society’s relationship with the natural world. Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant argues that this shift brought about within the Enlightenment was characterized by a dualistic and mechanistic understanding of nature, which positioned it as an object to be controlled, exploited, and dominated by humans. She touches on ideas such as mastery over nature, the conquest of wilderness, and the instrumentalization of natural resources. See Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (New York: HarperOne, 1980).

21 Fredric Jameson, “Future City,” New Left Review, no. 21 (2003): 76.

22 Environmental historian and historical geographer Jason W. Moore is an important figure within this discourse that maintains capitalism is fundamentally a world-ecology system. Moore challenges the common understanding of capitalism as solely an economic and social system and argues that it must be understood as an ecological regime that operates through a web of life. See Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London, UK: Verso, 2015).

23 Sociologist John Bellamy Foster provides insight into Marx's analysis of capitalism as a social system that degrades and alienates both labor and nature within Marx’s concept of metabolic rift. This reevaluation of orthodox Marxism demonstrates the interconnected crises of capitalism, including ecological degradation, social inequality, and alienation. See John Bellamy Foster, "Marx's Ecology: Materialism and Nature," Monthly Review 47, no. 3 (1995): 111–20.

24 Bertell Ollman, Alienation: Marx’s Conception of Man in Capitalist Society, (London: Cambridge University Press, 1971).

25 Francois Roche, “mythomaniaS _ 2012-2017,” Props /newt Francois Roche, 2017, https://www.new-territories.com/props.htm.

26 Andrés Jaque, “Rambla Climate-House,” Office for Political Innovation, 2021, https://officeforpoliticalinnovation.com/work/marblelous-crowned-house/.

27 Ibid.

28 Kenneth Frampton, "Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance," Perspecta, 20 (1983): 18–34.

29 This is an analysis of the complex relationship between agriculture and political history to critically examine the concepts of rootedness and mobility in the context of landscape theory. See Francesca Bray et al., “Cropscapes and History : Reflections on Rootedness and Mobility,” Transfers 9, no. 1 (2019): 20–41, https://doi.org/10.3167/trans.2019.090103

Reese Lewis

Theories On Grain Silos And Chat Mountains: A Comparative Analysis

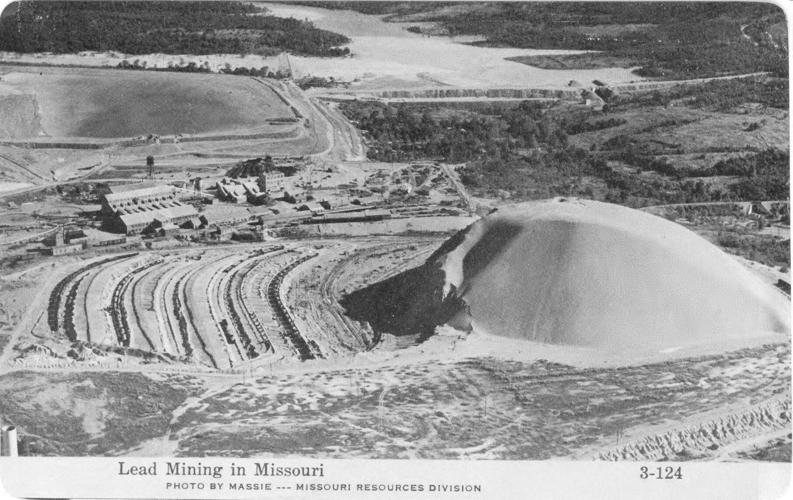

Just as European architects found syntax for a modernist language in the grain silos of the United States landscape, another mountainous form was taking shape that would also come to stand in contrast to the horizontality of the US Midwest. Dotted throughout the midwestern landscape now sit nearly 100-year-old towering mountains of siliceous rock, limestone, and heavy metal waste from industrial led and zinc mining operations. Colloquially termed “chat,” these mountains of toxic dust emerge from the countryside as headstones for the dead communities throughout the 2,500 square miles of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. These regions were destroyed by industrialization-induced pollution from these mining operations and abandoned by the neoliberal free flow of global capital during deindustrialization.

European modernists of the 1910s and 20s studied US factories and grain silos at a near-obsessive level because the rationalism of their forms were signs of theoretical meaning that lied within the political economy of the epoch. There was a great common idea that the unprecedented technological innovations seen in the late 19th and early 20th were the greatest tools for securing natural resources necessary for industrial production and socio-economic progress for the nation-state. In response, architects of this period became interested in the metaphysics of pure geometry that signaled the utopian promises associated with industrial capitalism.1 This mode of formal analysis of industrial structures was meant to be deployed for architects to develop an architectural language in line with the technical and scientific epoch they saw emerging.

Now we are seeing the consequences of this insatiable thirst for growth, such that global CO2 emissions and the destruction of global ecosystems have prompted an environmental crisis that poses an existential threat to all life on Earth. This is the primary cultural, psychological, political, social, and economic framework that should direct an architecture sensitive to the current moment. So just as modern architectural theorists argued that the US grain silos were a precursor to the international style of modernist architecture, chat mountains can be utilized as objects of study that represent the naturalizing process of capitalist production and the semiotics of ecosystems and landscapes in order to inform an architecture that is responding to the structural conditions of the moment. Put simply, grain silos stood in for the myth of the utopian promise of capitalist growth within the early 20th century, chat mountains represent the failure of this myth and the consequences of that aspiration to be found in the 21st century.

The theory developed here advocates for an architecture of ecological defamiliarization.2 This is an architecture that calls for introducing foreign ecological and biological elements into a landscape to directly remediate our history of producing waste landscapes. This approach is based on extracting lessons from chat mountains and the consequences of capitalist accumulation on the environment. What has become local, familiar, and colloquial within the Anthropocene—meaning not alien to our landscape—are pollutants, a term that signifies what is foreign to a healthy condition. This contradiction must be destabilized by breaking from our everyday familiarity with a poison-soaked landscape and atmosphere. Architecture’s role is then best used as a framework for plant life and landform that invade and disrupt these ordinary material and psychological conditions.

The History Of Chat Mountains

The history of how chat mountains came into being and eventually became abandoned is the story of the environmental outcome of industrial capitalism, followed by the deindustrialization of the West under neoliberalism.3 This historicity serves to highlight how landscapes such as the US midwest became ideological wastelands. Within this process of resource extraction and industrial production, these hinterlands produced a new landscape, a new naturalized imagination of what urban and rural populations came to understand as natural elements under the influence of late-stage capitalism.

Chat mountains, or piles of granular mine tailings composed of lead, zinc, and cadmium contaminants, have become the dominant geographic feature of the Tri-State Mining District. The tri-state region covers approximately 2,500 square miles and includes parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. With the first commercial ore discovery in the Tri-State made in southwestern Missouri around 1838, the mines largely supplied metal for US war efforts and the expanding national railroad system. Its most common use is for galvanization of coating steel and iron as well as other metals to prevent rust and corrosion. The mountains are formed after the excavated rock is processed and the metal ore extracted, the mining tailings that remained were deposited into piles that were up to 200 feet in height. The mill operations processed lead and zinc ores, crushing and separating them until all that remained was a gravel-like substance. Elevators and conveyors took this chat out of the mines and dumped it into piles. An inventory conducted by the EPA in 2005 identified 83 chat piles occupying 767 acres, and 243 chat bases (or former piles) occupying 2,079 acres.4

Chat mountains are what landscape and urban design scholars Charles Waldheim and Alan Berger would identify as a product of the rupture in rural and urban form shifts in the dominant modes of capitalist production.5 The first period is characterized by Fordist industrial production within national markets, heavily regulated economies, and relatively stable labor relations. What followed was a period of mature decentralized Fordism in the 1970s where a reliance on international trade and neo-liberal economic policies allowed the outsourcing of labor internationally, flexible or informal labor arrangements, and increasing global capital flows. Each period left previous spatial modes obsolete and abandoned in their wake. Production in the Tri-State Mining District gradually declined post-war, and in 1970, the last active mine, near Baxter Springs, Kansas, shut down due to environmental and economic difficulties.6 Growing competition from overseas mining leveraged the low labor costs of production in countries with less strict labor and human rights laws. Much industrial production during this period in the US moved overseas.

These metallic mountains remain exposed to the surrounding environment, where wind and rain carry the lead into the ground, surface water, groundwater, and air. Prolonged exposure to lead has been recorded to cause learning disabilities and impairments to the immune, circulatory, and nervous systems among individuals exposed to these affected environments. Children, in particular, are the most susceptible to the detrimental consequences of such exposure.

To counter these harmful effects, the Environmental Protection Agency began large-scale clean-up and remediation projects in the region in the 1980s. The EPA also classified three major Superfund sites in the Tar Creek mine of northeast Oklahoma; the Jasper County and Newton County sites in southwest Missouri; and the Cherokee County site in southeast Kansas. In addition, large areas have been rendered uninhabitable due to damage to air, land, and water quality. In areas such as Picher, Oklahoma, groundwater and air contamination warranted the EPA in 2009 to evacuate the town and relocate all its residents.7

Despite the significant health impacts on local residents, it was not until the 1990s when the EPA made these environmental and health risks known to the public. Prior to this awareness, local residents often used these mountains for recreational purposes much like any other elevated landscape feature. They were seen as social and leisure spaces where the residents of the town regularly enjoyed picnics, cycling, and holiday celebrations, and sometimes added the dust that made up the Chatchat mountains into children’s sandboxes. For almost a century, town residents were not aware the dust was poisonous.

The extracting and processing of zinc and lead ore that is then smelt and refined in processing plants is understood to produce a final product that is highly “unnatural.” But what the chat mountains reveal, both in the beginning process of extraction and the final product of waste, is that industrial processes are unable to avoid engagement with the forces and materiality of nature. Here it is geology then physics and hydrology. These natural resources taken within the crust of the earth are industrially processed, left exposed to the laws of gravity, entropy, chemistry, and so on, and produce a form and materiality which have an uncanny resemblance to mountains formed by the movement of tectonic plates. Within psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freund conceives of the uncanny as the compulsion to repeat. This refers to the persistence of unconscious thoughts and their ability to evade even the most determined forms of repression. The archetype of the uncanny is often the zombie, not a new thing; it is always an old, and usually repressed thing that recurs in the place where it is not expected.8 In a landscape dominated by monoculture agriculture, any semblences of a diverse ecosystem had been razed from the consciousness of local inhabitants, such that alienation from wilderness had been long repressed. But chat mountains returned as zombies in the landscape as near to real mountains. It is this uncanny resemblance, the timeframe in which they have existed, and an intimacy with using nature as a tool for industrial production (largely industrial agriculture of the Midwest) that make these mountains, within the unconsciousness of local residents, naturalized into the landscape.

Local residents associate these mountains of industrial waste with geological formations resulting from large-scale movements of tectonic plates, folding, faulting, volcanic activity, igneous intrusion, and metamorphism —the creation of real mountains. This slippage in semiotics reveals the limitations of language in signaling what is natural and in understanding the built and non-built environment. In the metaphysics of their materiality, a theory on a new architecture can be extracted just as the European modernists looked to the natural laws of US engineering present in forming the legible geometry of grain silos. The methodology for studying buildings can also be extracted from the modernist analysis of grain silos and applied to chat mountains since they are not unlike most their human-made artifacts just as the grain silos were artifacts of industrial progress.

Grain Silos as Objects of Study

Reyner Banham’s argument for the influence of US industrial grain elevators on the invention of the International Style of European modernism in Concrete Atlantis begins with Walter Gropius’ design Faguswerke at Alfeld-an-der-Leine in northwest Germany. Upon the completion of the factory, Gropius published an article and illustrations called “Die Entwicklung Moderner Industriebaukunst” (“The Development of Modern Industrial Architecture”) as part of the journal Jahrbuch Des Deutschen Werkbundes that effectively introduced American industrial buildings to the European architectural profession and public.9 This obsession with US industrial progress and innovation came from technological advancements that improved production efficiencies and spurred capital growth. As latecomers to the industrialization process, European nations sought to remain competitive amidst a period of fierce nationalistic competition for economic expansion. Traveling across the Atlantic in the form of images in trade publications, from the concrete industry and newspaper clippings, and spread within Europe, the US grain silos represented monumental objects large and complex enough, yet also rational enough to engage the imagination and moral sensibilities of European modernists seeking symbolic content that indicated the promises of technical production and capital accumulation. As Banham argues, these grain silos and factories set modernists such as Walter Gropius, Waler Curt Behrendt Berhendt, Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn, Moisei Ginzburg, and Edoardo Persico “to meditating on the necessary laws of industry, architecture, man, and the universe.”10

Interests in aesthetics at the time were focused on monumental art, which was put forward by art historians Wilhelm Worringer and Alois Riegl.11 In Worringer’s comparison between America and Egypt, he positioned geometric abstraction in line with the ideological ambitions for progress of the period. This connection between architectural discourse and art history of the period was made evident when Gropius argued that “the newest work halls of the great North American industrial trusts can almost bear comparison with the work of the ancient Egyptians in their overwhelming monumental power.”12 This comparison was meant to link the modern scientific individual with their rationalistic cognition, which for Gropius was best represented by the US engineers who designed these structures, with the historical tendency of primitive art forms towards geometric abstraction and strict proportionality of parts.

Contemporary Art, Chat Mountains, and The New Ecologies Movement

So just as Gropius had made connections between contemporary art and the platonic qualities of the US grain elevator, so too can the connection between chat mountains and contemporary art discourse be made. Artists such as Pierre Huygue, Mel Chin, Michael E. Smith, Hito Steyerl, and Hugh Hayden all participated in producing relational ecological environments between agents, whether that be institutions, plant life, animals, and viewers. Their work is concerned with producing or critiquing the semiotics of nature, revealing that constructed environments always tend towards becoming second nature in the imagination of individuals.

While the initial tendency would be to categorize this artistic movement within the contemporary art historical discourse around objecthood, but for the critical tools necessary here is important to consider that this work primarily works with the historical process, technological advancements, and socio-economic forces that have estranged society from the natural realm. This then in fact sets up a critique of the dominant philosophical position within contemporary art called new materialism. This has become one of the prevailing modes of art criticism today that encompasses Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) and Speculative Realism headed by philosophers Timothy Morton and Graham Harman. This philosophical school of thought emphasizes the composition, vitality, materiality, autonomy, wonder, and durability of objects, while placing all things on the same ontological plane. As Graham Harman argues in The Quadruple Object, “While there may be an infinity of objects in the cosmos, they come in only two kinds: the real object that withdraws from all experience and the sensual object that exists only in experience.”13 However, theorist Andrew Cole outlines the movement’s misinterpretation of Kantian epistemology, contending that, in fact, OOO could provide support for Kant’s position on understanding the world.14 There are certainly object relations, but humans can only allude to them in our inevitably human way. It is possible to think the unthinkable if we adopt “allusion” or other “oblique approaches” towards the object world, which we cannot directly experience.15 Consequently, human beings can never escape an anthropocentric understanding of the world and its objects.

An architectural theory based on historical analysis of Chatchat mountains does not place the matter that makes up these forms on the same ontological plane as humans. Understanding the historical and structural conditions that led to the accumulation of those piles of industrial waste, the agency of this dust cannot be compared to the force of industrial and neoliberal capital accumulation that produced them. This approach would avoid what Karl Marx called the “mystical character of the commodity,” which stems from the tendency to personify an object’s inner properties while ignoring the broader historical processes that define its commoditization commoditation. This is the metaphysics of the capitalist form.16 As Cole argues:

Ours is a time when schools of interpretation ask us to personify and caricature objects as autonomous and alive—whether they are the objects who ‘speak’ in the new so-called vibrant materialism, or objects who fuss and act up in actor-network theory, or objects with ‘primitive psyches’ in an object-oriented ontology. Is this really the way to think at this moment? For Marx, at least, this way of thinking about objects is what keeps capitalism ticking. To adopt such a philosophy, no questions asked, is fantasy—commodity fetishism in academic form. To identify such philosophy as the metaphysics of capitalism is theory ever attentive to history’s impress on our imaginations, whatever we may dream.17

Rather than focusing on analyzing the agency and complex internal qualities of relations inherent in these piles of dust, we can, as Gropius prompts us to, understand that:

All material things are no more than serviceable aids, with which everyday sensory impressions can reach higher mental states, even become artistic drives… Art needs belief in some great common idea with which to achieve the heights. To receive a deep impression from a building, we must have belief in the idea that it presents18

The idea that chat mountains present is the imaginative capacity of capitalism to naturalize itself, replacing nature. Chat mountains are myth-making devices; truly not objects, ideas, or concepts, but rather forms of signification (a process rather than a thing) largely because they present themselves as always have been there and appeared to simply occur without any historical determination. This speaks to the literary critique of Roland Barthes development of a concept of myth, where its key principle is to transform history into nature.19 Resource extraction and industrial waste production such as chat mountains have become the new landscape in the late-stage Anthropocene, where any alternative form that does not instrumentalize ecosystems seems unimaginable and unnatural.20 As Frederic Jameson quipped, “Someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.”21 Ecosystems, atmospheres, soil, waterways, and geologies no longer exist without capitalism’s touch. An original state, a first nature of true wilderness, is no longer possible.22 Furthermore, we could revise this statement again since we are in a moment where the structural track we are on is taking us to our own global demise. We have already irreparably damaged the planet to such an extent that it is easier to imagine the end of nature than to imagine the end of capitalism.

An Architecture of Ecological Defamiliarization

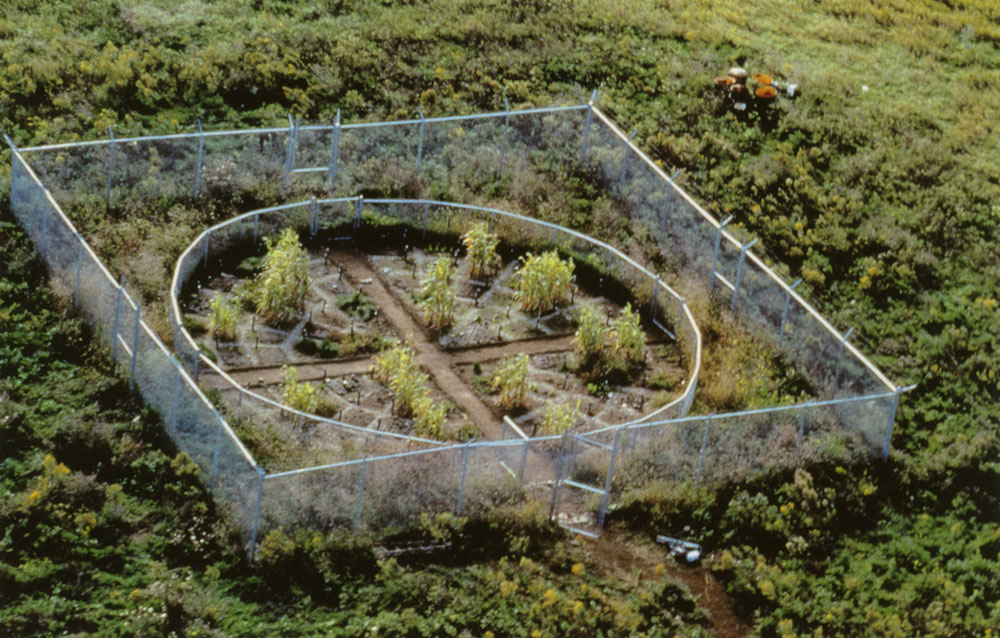

This discourse demonstrates that Marx's materialist analysis reveals capitalism to be a social system that estranges individuals not only from their own productive activities, the products they create, and other individuals but also from the natural environment. This provides insights into the interconnected crises of ecological degradation and alienation.23 Architect François Roche’s work is concerned with this inquiry into the contradictions of modern nature: a partly human artifice, upon which we depend materially, extending our being and life, but also foreign and strange, privatized in a myriad of forms. He often seesaws between attempts to overcome alienation (the condition of being expropriated from our very own means of laboring in and with the earth) and heightening it.24 Roche’s idea is that we assume nature to be domesticated, purely sympathetic, and predictable to human needs. Consequently, he believes it is necessary to confront society with its unconscious paranoia of being alienated from the natural realm. This confrontation is achieved by introducing a new nature that produces a “psycho-repulsion.”25 This architectural approach is most evident in his project “Lost” in Paris, where he converted a courtyard home in Paris with a skin of grotesquely dense vegetation. Here we see the techniques of ecological defamiliarization deployed as Roche deploys an absurd amount of plants to camouflage his building. His architecture no longer operates as an environmental barrier, but itself becomes an ecosystem that is making odd the historical conditions of Parisian urban planning with an overly wild, overabundance, aggressive and combative use of plant life.

We can also see an ambition to understand architecture as infrastructure for environmental production with the work of Andres Jaque/Office of Political Innovation. With projects like Reggio School, Landscape Condenser, COSMO MoMA PS1, and larger scale iterations like the Demonstrative Techno-Floresta in the Bogotá Botanical Garden, their work is often concerned with gathering heterogeneous ecosystems and climates into a singular structure. Particularly with The Rambla Climate-House, Jaque calls this architecture “a climatic and ecological device.”26 This house collects pooled rainfall from its roofs and grey water from its showers and sinks to spray onto the ravines (ramblas) below in order to “regenerate their former ecologic and climatic constitution.”27 Their state of nature before the growth of speculative real estate in the area created suburbs.

Jaque’s position within all of this work is to create environmental scenarios that return to their originalorginal state, to reintroduce ecosystems that were once familiar to the landscapes before human exploitation. But an architecture of ecological defamiliarization counters any nativist or essentialist notion of environmental production through the building. What this calls for is an invasive, combative approach to environmental remediation.

Jaque’s position within all of this work is to create environmental scenarios that return to their originalorginal state, to reintroduce ecosystems that were once familiar to the landscapes before human exploitation. But an architecture of ecological defamiliarization counters any nativist or essentialist notion of environmental production through the building. What this calls for is an invasive, combative approach to environmental remediation.

Within the post-modern rejection of modernity’s emphasis on globalization and placelessness during the 1980s, Critical regionalism rejected the universalizing tendency of international-style architecture and maintains a nativist approach to ecological production from the built environment.28 This methodological framework has become foundational to a great deal of contemporary environmental discourse within architecture. But critical regionalism does not account for not only the geographic movement of plant life under modernity but also doesn’t account for temporal mobility, which inherently transforms ecosystems under capitalism. The historical analysis of science and agriculture provides a methodological framework for the ideas behind mobility studies.29 A particular focus on the study object of crops serves as a representation of natural resources that have been instrumentalized for human use, encompassing the entirety of what was formerly wilderness within the late-stage capitalism of the Anthropocene. The specific characteristics of crops are inseparably natural and social, inescapably material, yet inherently symbolic, at once rooted and mobile, suggesting many fruitful ways to engage with mobility and with the relations between mobility and rootedness. This geographic-historical understanding makes the very foundation of site-specificity unstable and mobile. Consider the irreparable process of global desertification, which serves as an example of an ecosystem both geographically and temporarily mobile due to human-induced transformations of ecosystems. In the context of climate change, the notion of site-specificity becomes fleeting and constantly evolving, necessitating a universal approach to address the totalizing condition of global climate change. Simultaneously, what is necessary for responding to the specificities of ecological remediation, meaning the forms of regional resource extraction, requires specific forms of environmental remediation and a choice of plant life that considers local climate and pollution alike. The mobility of plantlife and radical transformation of local climates extend the techniques of defamiliarization into a non-essentialist selection of plant life with the architecture since the ecosystem it introduces itself will be unfamiliar to a local context.

With this understanding of the mobility of plantlife under the Anthropocene, and the phytoremediation necessary to address pollution in a particular region, architecture then becomes an infrastructure for alien plantlife. This is to counter the tendency of the rationalist and instrumental modern relationship with ecosystems under capitalism to naturalize itself. In response, we must become refamiliar with the otherness of plant life. Here defamiliarization of what has become familiar or taken for granted, and hence automatically perceived, is to make strange the instrumentalization of the biological realm to be in service of human needs. A theory for an architecture of ecological defamiliarization considers the important historical and psychic conditions associated with ecological imagination and semiotics in the Anthropocene. What is unfamiliar is what breaks the chains of signifiers in a landscape where pollution, waste, and resource extraction have become naturalized.

Reese Lewis (b. Calgary, Alberta) holds a Master of Architecture from Princeton University where he was awarded the School of Architecture History and Theory Prize and the Suzanne Kolarik Underwood Thesis Prize. He is currently an architect and writer based in New York City. His research and design work is primarily concerned with the conflict between European Enlightenment epistemology and the settler-colonial landscape.

A Dust Atlantis: Chat Mountains and An Architecture of Ecological Defamiliarization

Theories On Grain Silos And Chat Mountains: A Comparative Analysis

Just as European architects found syntax for a modernist language in the grain silos of the United States landscape, another mountainous form was taking shape that would also come to stand in contrast to the horizontality of the US Midwest. Dotted throughout the midwestern landscape now sit nearly 100-year-old towering mountains of siliceous rock, limestone, and heavy metal waste from industrial led and zinc mining operations. Colloquially termed “chat,” these mountains of toxic dust emerge from the countryside as headstones for the dead communities throughout the 2,500 square miles of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. These regions were destroyed by industrialization-induced pollution from these mining operations and abandoned by the neoliberal free flow of global capital during deindustrialization.

European modernists of the 1910s and 20s studied US factories and grain silos at a near-obsessive level because the rationalism of their forms were signs of theoretical meaning that lied within the political economy of the epoch. There was a great common idea that the unprecedented technological innovations seen in the late 19th and early 20th were the greatest tools for securing natural resources necessary for industrial production and socio-economic progress for the nation-state. In response, architects of this period became interested in the metaphysics of pure geometry that signaled the utopian promises associated with industrial capitalism.1 This mode of formal analysis of industrial structures was meant to be deployed for architects to develop an architectural language in line with the technical and scientific epoch they saw emerging.

Now we are seeing the consequences of this insatiable thirst for growth, such that global CO2 emissions and the destruction of global ecosystems have prompted an environmental crisis that poses an existential threat to all life on Earth. This is the primary cultural, psychological, political, social, and economic framework that should direct an architecture sensitive to the current moment. So just as modern architectural theorists argued that the US grain silos were a precursor to the international style of modernist architecture, chat mountains can be utilized as objects of study that represent the naturalizing process of capitalist production and the semiotics of ecosystems and landscapes in order to inform an architecture that is responding to the structural conditions of the moment. Put simply, grain silos stood in for the myth of the utopian promise of capitalist growth within the early 20th century, chat mountains represent the failure of this myth and the consequences of that aspiration to be found in the 21st century.

The theory developed here advocates for an architecture of ecological defamiliarization.2 This is an architecture that calls for introducing foreign ecological and biological elements into a landscape to directly remediate our history of producing waste landscapes. This approach is based on extracting lessons from chat mountains and the consequences of capitalist accumulation on the environment. What has become local, familiar, and colloquial within the Anthropocene—meaning not alien to our landscape—are pollutants, a term that signifies what is foreign to a healthy condition. This contradiction must be destabilized by breaking from our everyday familiarity with a poison-soaked landscape and atmosphere. Architecture’s role is then best used as a framework for plant life and landform that invade and disrupt these ordinary material and psychological conditions.

The History Of Chat Mountains

The history of how chat mountains came into being and eventually became abandoned is the story of the environmental outcome of industrial capitalism, followed by the deindustrialization of the West under neoliberalism.3 This historicity serves to highlight how landscapes such as the US midwest became ideological wastelands. Within this process of resource extraction and industrial production, these hinterlands produced a new landscape, a new naturalized imagination of what urban and rural populations came to understand as natural elements under the influence of late-stage capitalism.

Chat mountains, or piles of granular mine tailings composed of lead, zinc, and cadmium contaminants, have become the dominant geographic feature of the Tri-State Mining District. The tri-state region covers approximately 2,500 square miles and includes parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. With the first commercial ore discovery in the Tri-State made in southwestern Missouri around 1838, the mines largely supplied metal for US war efforts and the expanding national railroad system. Its most common use is for galvanization of coating steel and iron as well as other metals to prevent rust and corrosion. The mountains are formed after the excavated rock is processed and the metal ore extracted, the mining tailings that remained were deposited into piles that were up to 200 feet in height. The mill operations processed lead and zinc ores, crushing and separating them until all that remained was a gravel-like substance. Elevators and conveyors took this chat out of the mines and dumped it into piles. An inventory conducted by the EPA in 2005 identified 83 chat piles occupying 767 acres, and 243 chat bases (or former piles) occupying 2,079 acres.4

Chat mountains are what landscape and urban design scholars Charles Waldheim and Alan Berger would identify as a product of the rupture in rural and urban form shifts in the dominant modes of capitalist production.5 The first period is characterized by Fordist industrial production within national markets, heavily regulated economies, and relatively stable labor relations. What followed was a period of mature decentralized Fordism in the 1970s where a reliance on international trade and neo-liberal economic policies allowed the outsourcing of labor internationally, flexible or informal labor arrangements, and increasing global capital flows. Each period left previous spatial modes obsolete and abandoned in their wake. Production in the Tri-State Mining District gradually declined post-war, and in 1970, the last active mine, near Baxter Springs, Kansas, shut down due to environmental and economic difficulties.6 Growing competition from overseas mining leveraged the low labor costs of production in countries with less strict labor and human rights laws. Much industrial production during this period in the US moved overseas.

These metallic mountains remain exposed to the surrounding environment, where wind and rain carry the lead into the ground, surface water, groundwater, and air. Prolonged exposure to lead has been recorded to cause learning disabilities and impairments to the immune, circulatory, and nervous systems among individuals exposed to these affected environments. Children, in particular, are the most susceptible to the detrimental consequences of such exposure.

To counter these harmful effects, the Environmental Protection Agency began large-scale clean-up and remediation projects in the region in the 1980s. The EPA also classified three major Superfund sites in the Tar Creek mine of northeast Oklahoma; the Jasper County and Newton County sites in southwest Missouri; and the Cherokee County site in southeast Kansas. In addition, large areas have been rendered uninhabitable due to damage to air, land, and water quality. In areas such as Picher, Oklahoma, groundwater and air contamination warranted the EPA in 2009 to evacuate the town and relocate all its residents.7

Despite the significant health impacts on local residents, it was not until the 1990s when the EPA made these environmental and health risks known to the public. Prior to this awareness, local residents often used these mountains for recreational purposes much like any other elevated landscape feature. They were seen as social and leisure spaces where the residents of the town regularly enjoyed picnics, cycling, and holiday celebrations, and sometimes added the dust that made up the Chatchat mountains into children’s sandboxes. For almost a century, town residents were not aware the dust was poisonous.

The extracting and processing of zinc and lead ore that is then smelt and refined in processing plants is understood to produce a final product that is highly “unnatural.” But what the chat mountains reveal, both in the beginning process of extraction and the final product of waste, is that industrial processes are unable to avoid engagement with the forces and materiality of nature. Here it is geology then physics and hydrology. These natural resources taken within the crust of the earth are industrially processed, left exposed to the laws of gravity, entropy, chemistry, and so on, and produce a form and materiality which have an uncanny resemblance to mountains formed by the movement of tectonic plates. Within psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freund conceives of the uncanny as the compulsion to repeat. This refers to the persistence of unconscious thoughts and their ability to evade even the most determined forms of repression. The archetype of the uncanny is often the zombie, not a new thing; it is always an old, and usually repressed thing that recurs in the place where it is not expected.8 In a landscape dominated by monoculture agriculture, any semblences of a diverse ecosystem had been razed from the consciousness of local inhabitants, such that alienation from wilderness had been long repressed. But chat mountains returned as zombies in the landscape as near to real mountains. It is this uncanny resemblance, the timeframe in which they have existed, and an intimacy with using nature as a tool for industrial production (largely industrial agriculture of the Midwest) that make these mountains, within the unconsciousness of local residents, naturalized into the landscape.

Local residents associate these mountains of industrial waste with geological formations resulting from large-scale movements of tectonic plates, folding, faulting, volcanic activity, igneous intrusion, and metamorphism —the creation of real mountains. This slippage in semiotics reveals the limitations of language in signaling what is natural and in understanding the built and non-built environment. In the metaphysics of their materiality, a theory on a new architecture can be extracted just as the European modernists looked to the natural laws of US engineering present in forming the legible geometry of grain silos. The methodology for studying buildings can also be extracted from the modernist analysis of grain silos and applied to chat mountains since they are not unlike most their human-made artifacts just as the grain silos were artifacts of industrial progress.

Grain Silos as Objects of Study

Reyner Banham’s argument for the influence of US industrial grain elevators on the invention of the International Style of European modernism in Concrete Atlantis begins with Walter Gropius’ design Faguswerke at Alfeld-an-der-Leine in northwest Germany. Upon the completion of the factory, Gropius published an article and illustrations called “Die Entwicklung Moderner Industriebaukunst” (“The Development of Modern Industrial Architecture”) as part of the journal Jahrbuch Des Deutschen Werkbundes that effectively introduced American industrial buildings to the European architectural profession and public.9 This obsession with US industrial progress and innovation came from technological advancements that improved production efficiencies and spurred capital growth. As latecomers to the industrialization process, European nations sought to remain competitive amidst a period of fierce nationalistic competition for economic expansion. Traveling across the Atlantic in the form of images in trade publications, from the concrete industry and newspaper clippings, and spread within Europe, the US grain silos represented monumental objects large and complex enough, yet also rational enough to engage the imagination and moral sensibilities of European modernists seeking symbolic content that indicated the promises of technical production and capital accumulation. As Banham argues, these grain silos and factories set modernists such as Walter Gropius, Waler Curt Behrendt Berhendt, Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn, Moisei Ginzburg, and Edoardo Persico “to meditating on the necessary laws of industry, architecture, man, and the universe.”10

Interests in aesthetics at the time were focused on monumental art, which was put forward by art historians Wilhelm Worringer and Alois Riegl.11 In Worringer’s comparison between America and Egypt, he positioned geometric abstraction in line with the ideological ambitions for progress of the period. This connection between architectural discourse and art history of the period was made evident when Gropius argued that “the newest work halls of the great North American industrial trusts can almost bear comparison with the work of the ancient Egyptians in their overwhelming monumental power.”12 This comparison was meant to link the modern scientific individual with their rationalistic cognition, which for Gropius was best represented by the US engineers who designed these structures, with the historical tendency of primitive art forms towards geometric abstraction and strict proportionality of parts.

Contemporary Art, Chat Mountains, and The New Ecologies Movement

So just as Gropius had made connections between contemporary art and the platonic qualities of the US grain elevator, so too can the connection between chat mountains and contemporary art discourse be made. Artists such as Pierre Huygue, Mel Chin, Michael E. Smith, Hito Steyerl, and Hugh Hayden all participated in producing relational ecological environments between agents, whether that be institutions, plant life, animals, and viewers. Their work is concerned with producing or critiquing the semiotics of nature, revealing that constructed environments always tend towards becoming second nature in the imagination of individuals.

While the initial tendency would be to categorize this artistic movement within the contemporary art historical discourse around objecthood, but for the critical tools necessary here is important to consider that this work primarily works with the historical process, technological advancements, and socio-economic forces that have estranged society from the natural realm. This then in fact sets up a critique of the dominant philosophical position within contemporary art called new materialism. This has become one of the prevailing modes of art criticism today that encompasses Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) and Speculative Realism headed by philosophers Timothy Morton and Graham Harman. This philosophical school of thought emphasizes the composition, vitality, materiality, autonomy, wonder, and durability of objects, while placing all things on the same ontological plane. As Graham Harman argues in The Quadruple Object, “While there may be an infinity of objects in the cosmos, they come in only two kinds: the real object that withdraws from all experience and the sensual object that exists only in experience.”13 However, theorist Andrew Cole outlines the movement’s misinterpretation of Kantian epistemology, contending that, in fact, OOO could provide support for Kant’s position on understanding the world.14 There are certainly object relations, but humans can only allude to them in our inevitably human way. It is possible to think the unthinkable if we adopt “allusion” or other “oblique approaches” towards the object world, which we cannot directly experience.15 Consequently, human beings can never escape an anthropocentric understanding of the world and its objects.

An architectural theory based on historical analysis of Chatchat mountains does not place the matter that makes up these forms on the same ontological plane as humans. Understanding the historical and structural conditions that led to the accumulation of those piles of industrial waste, the agency of this dust cannot be compared to the force of industrial and neoliberal capital accumulation that produced them. This approach would avoid what Karl Marx called the “mystical character of the commodity,” which stems from the tendency to personify an object’s inner properties while ignoring the broader historical processes that define its commoditization commoditation. This is the metaphysics of the capitalist form.16 As Cole argues:

Ours is a time when schools of interpretation ask us to personify and caricature objects as autonomous and alive—whether they are the objects who ‘speak’ in the new so-called vibrant materialism, or objects who fuss and act up in actor-network theory, or objects with ‘primitive psyches’ in an object-oriented ontology. Is this really the way to think at this moment? For Marx, at least, this way of thinking about objects is what keeps capitalism ticking. To adopt such a philosophy, no questions asked, is fantasy—commodity fetishism in academic form. To identify such philosophy as the metaphysics of capitalism is theory ever attentive to history’s impress on our imaginations, whatever we may dream.17

Rather than focusing on analyzing the agency and complex internal qualities of relations inherent in these piles of dust, we can, as Gropius prompts us to, understand that:

All material things are no more than serviceable aids, with which everyday sensory impressions can reach higher mental states, even become artistic drives… Art needs belief in some great common idea with which to achieve the heights. To receive a deep impression from a building, we must have belief in the idea that it presents18

The idea that chat mountains present is the imaginative capacity of capitalism to naturalize itself, replacing nature. Chat mountains are myth-making devices; truly not objects, ideas, or concepts, but rather forms of signification (a process rather than a thing) largely because they present themselves as always have been there and appeared to simply occur without any historical determination. This speaks to the literary critique of Roland Barthes development of a concept of myth, where its key principle is to transform history into nature.19 Resource extraction and industrial waste production such as chat mountains have become the new landscape in the late-stage Anthropocene, where any alternative form that does not instrumentalize ecosystems seems unimaginable and unnatural.20 As Frederic Jameson quipped, “Someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.”21 Ecosystems, atmospheres, soil, waterways, and geologies no longer exist without capitalism’s touch. An original state, a first nature of true wilderness, is no longer possible.22 Furthermore, we could revise this statement again since we are in a moment where the structural track we are on is taking us to our own global demise. We have already irreparably damaged the planet to such an extent that it is easier to imagine the end of nature than to imagine the end of capitalism.

An Architecture of Ecological Defamiliarization

This discourse demonstrates that Marx's materialist analysis reveals capitalism to be a social system that estranges individuals not only from their own productive activities, the products they create, and other individuals but also from the natural environment. This provides insights into the interconnected crises of ecological degradation and alienation.23 Architect François Roche’s work is concerned with this inquiry into the contradictions of modern nature: a partly human artifice, upon which we depend materially, extending our being and life, but also foreign and strange, privatized in a myriad of forms. He often seesaws between attempts to overcome alienation (the condition of being expropriated from our very own means of laboring in and with the earth) and heightening it.24 Roche’s idea is that we assume nature to be domesticated, purely sympathetic, and predictable to human needs. Consequently, he believes it is necessary to confront society with its unconscious paranoia of being alienated from the natural realm. This confrontation is achieved by introducing a new nature that produces a “psycho-repulsion.”25 This architectural approach is most evident in his project “Lost” in Paris, where he converted a courtyard home in Paris with a skin of grotesquely dense vegetation. Here we see the techniques of ecological defamiliarization deployed as Roche deploys an absurd amount of plants to camouflage his building. His architecture no longer operates as an environmental barrier, but itself becomes an ecosystem that is making odd the historical conditions of Parisian urban planning with an overly wild, overabundance, aggressive and combative use of plant life.

We can also see an ambition to understand architecture as infrastructure for environmental production with the work of Andres Jaque/Office of Political Innovation. With projects like Reggio School, Landscape Condenser, COSMO MoMA PS1, and larger scale iterations like the Demonstrative Techno-Floresta in the Bogotá Botanical Garden, their work is often concerned with gathering heterogeneous ecosystems and climates into a singular structure. Particularly with The Rambla Climate-House, Jaque calls this architecture “a climatic and ecological device.”26 This house collects pooled rainfall from its roofs and grey water from its showers and sinks to spray onto the ravines (ramblas) below in order to “regenerate their former ecologic and climatic constitution.”27 Their state of nature before the growth of speculative real estate in the area created suburbs.

Within the post-modern rejection of modernity’s emphasis on globalization and placelessness during the 1980s, Critical regionalism rejected the universalizing tendency of international-style architecture and maintains a nativist approach to ecological production from the built environment.28 This methodological framework has become foundational to a great deal of contemporary environmental discourse within architecture. But critical regionalism does not account for not only the geographic movement of plant life under modernity but also doesn’t account for temporal mobility, which inherently transforms ecosystems under capitalism. The historical analysis of science and agriculture provides a methodological framework for the ideas behind mobility studies.29 A particular focus on the study object of crops serves as a representation of natural resources that have been instrumentalized for human use, encompassing the entirety of what was formerly wilderness within the late-stage capitalism of the Anthropocene. The specific characteristics of crops are inseparably natural and social, inescapably material, yet inherently symbolic, at once rooted and mobile, suggesting many fruitful ways to engage with mobility and with the relations between mobility and rootedness. This geographic-historical understanding makes the very foundation of site-specificity unstable and mobile. Consider the irreparable process of global desertification, which serves as an example of an ecosystem both geographically and temporarily mobile due to human-induced transformations of ecosystems. In the context of climate change, the notion of site-specificity becomes fleeting and constantly evolving, necessitating a universal approach to address the totalizing condition of global climate change. Simultaneously, what is necessary for responding to the specificities of ecological remediation, meaning the forms of regional resource extraction, requires specific forms of environmental remediation and a choice of plant life that considers local climate and pollution alike. The mobility of plantlife and radical transformation of local climates extend the techniques of defamiliarization into a non-essentialist selection of plant life with the architecture since the ecosystem it introduces itself will be unfamiliar to a local context.

With this understanding of the mobility of plantlife under the Anthropocene, and the phytoremediation necessary to address pollution in a particular region, architecture then becomes an infrastructure for alien plantlife. This is to counter the tendency of the rationalist and instrumental modern relationship with ecosystems under capitalism to naturalize itself. In response, we must become refamiliar with the otherness of plant life. Here defamiliarization of what has become familiar or taken for granted, and hence automatically perceived, is to make strange the instrumentalization of the biological realm to be in service of human needs. A theory for an architecture of ecological defamiliarization considers the important historical and psychic conditions associated with ecological imagination and semiotics in the Anthropocene. What is unfamiliar is what breaks the chains of signifiers in a landscape where pollution, waste, and resource extraction have become naturalized.

Reese Lewis (b. Calgary, Alberta) holds a Master of Architecture from Princeton University where he was awarded the School of Architecture History and Theory Prize and the Suzanne Kolarik Underwood Thesis Prize. He is currently an architect and writer based in New York City. His research and design work is primarily concerned with the conflict between European Enlightenment epistemology and the settler-colonial landscape.

<-